#WaybackWednesday: Press Your Luck

Christian Carrion shares his opinion of the lovable orange cat.

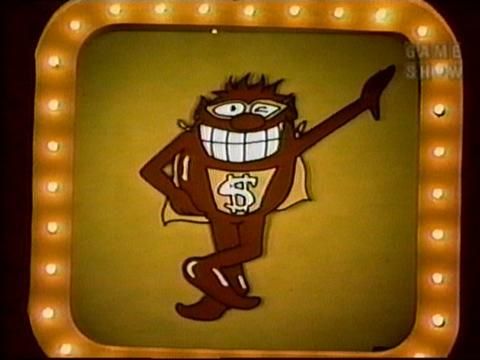

In the four decades since his hand-drawn debut, Jim Davis’ Garfield has evolved from a casserole-chomping cartoonist’s cat to cynical emblem of the work-a-day comic reader, an expertly-processed proto-meme that unites its fans in their mutual love of carbs and hatred of Mondays. By no means do I profess to know all the ingredients of Garfield’s lasagna of success. However, some key components that contribute to the feline’s seemingly perpetual popularity are arguably worthy of discussion.

Garfield is cute. His evolved form, from that of his initial walrus-like, Wilford Brimley-esque jowls and barely visible smile, now sports a pair of expressive, saucer-sized eyes a slim-yet-somehow-still-chubby frame, and a human-like mouth that lends itself to his many efforts at demeaning and demanding alike. This is no accident—after all, Garfield exists solely as the result of a push by creator Davis to come up with a “good, marketable character”. Davis, perhaps after looking at characters like Snoopy and Marmaduke and surmising that comic dogs have had their day, crafted Garfield in the image of one of the 25 cats he grew up with on an Indiana farm; injected him with the “large, cantankerous” personality of his grandfather, James A. Garfield Davis; and gave him a roommate in the form of an artist named Jon, after whom the comic strip was initially titled. By conjuring a character that filled the previously-unoccupied niche of appealing to the 15 million cat lovers in America at the time, Davis tapped into a stream of popularity—and revenue—that would eventually pay off at approximately one billion dollars per year.

Garfield is not funny. Garfield is drastically, emphatically not funny. This, again, is by design. The intention to make Garfield a genuinely humorous comic strip simply never existed. In fact, there was more of a concerted effort to make the comic strip not funny. The base model for the Garfield strip was Charles Schultz’s beloved Peanuts, although not the high-energy, piano-slapping, football-whiffing antics typified by the Charlie Brown gang’s TV counterpart. Davis had instead tried to mimic the “sunny, humorless monotony” of later Peanuts strips—the ones where Snoopy would lie on his doghouse, share a word or two with Woodstock, or perhaps have a daydream. Garfield’s merchandising potential always came first. The writing, which the 74-year-old Davis largely does on his own these days, is deliberately secondary.

Garfield is relatable. With his curated repertoire of foibles—work sucks, lasagna is good, I’m fat—Garfield, perhaps unknowingly, helped to usher in a new era of workplace humor. Perhaps propelled by the proliferation of personal computers in the office that tended to, in their infancy, confound users, as well as the then-burgeoning observational stand-up comedy scene pioneered by performers like David Brenner and Jerry Seinfeld, the Garfield strip infused blue-collar America with things to have in common with their fellow employee, a toolbox of tropes to be used in the often-necessary search for common ground with co-workers, classmates, colleagues. After all, do you know someone who hates lasagna?

Jim Davis once said, “An imagination is a powerful tool. It can tint memories of the past, shade perceptions of the present, or paint a future so vivid that it can entice…or terrify.” Thanks to the imagination of a cartoonist from Muncie, Indiana, the world has a fat furry feline friend who they can relate to, not laugh at, and enthusiastically purchase for many more years to come.