#tbt: Blockbusters

In this edition of Throwback Thursday, Christian Carrion takes a look at an ingenious game of speed and strategy, with letters that lead to victory.

“This is our last show on the air. On Monday…Las Vegas Gambit will be here, and Blockbusters following that, so…oh, no no, please don’t do that.”

On October 24, 1980, a young David Letterman braved a barrage of boos in Studio 6A as he announced that he was being replaced the following week by two game shows. Just four months earlier, Letterman’s morning comedy-talk show experiment, which itself had displaced High Rollers, Chain Reaction, and Hollywood Squares, had taken its first sarcastic step towards satellite stardom before falling flat on its nevertheless award-winning face. The David Letterman Show was praised and lauded by critics and diehard fans for its groundbreaking comedy writing (thanks in part to future stars Edie McClurg and Rich Hall, as well as head writer Merrill Markoe), but 80 episodes and a half-hour cutback later, NBC surmised that morning viewers wanted their bells and buzzers after all…and sent Dave, Bill Wendell and the NBC Symphony Orchestra packing. The move was probably for the best, in retrospect: The David Letterman Show, an off-the-wall affair rife with sarcasm, avant-garde musical acts and Stupid Pet Tricks, served as a prototype of much bigger and better things to come. Not to mention, game show fans of the early 80s would have never been introduced to the intriguing, entertaining, challenging game that is Blockbusters.

On October 24, 1980, a young David Letterman braved a barrage of boos in Studio 6A as he announced that he was being replaced the following week by two game shows. Just four months earlier, Letterman’s morning comedy-talk show experiment, which itself had displaced High Rollers, Chain Reaction, and Hollywood Squares, had taken its first sarcastic step towards satellite stardom before falling flat on its nevertheless award-winning face. The David Letterman Show was praised and lauded by critics and diehard fans for its groundbreaking comedy writing (thanks in part to future stars Edie McClurg and Rich Hall, as well as head writer Merrill Markoe), but 80 episodes and a half-hour cutback later, NBC surmised that morning viewers wanted their bells and buzzers after all…and sent Dave, Bill Wendell and the NBC Symphony Orchestra packing. The move was probably for the best, in retrospect: The David Letterman Show, an off-the-wall affair rife with sarcasm, avant-garde musical acts and Stupid Pet Tricks, served as a prototype of much bigger and better things to come. Not to mention, game show fans of the early 80s would have never been introduced to the intriguing, entertaining, challenging game that is Blockbusters.

A Goodson-Todman production, the format for Blockbusters was created by puzzle master Steve Ryan, who would find later fame as the puzzle designer on Classic Concentration, as well as the creator of the pricing game Now…or Then and several other games for use on state-run lottery game shows. Blockbusters had its roots in a much older board game called Hex, independently invented by John Nash of A Beautiful Mind fame in 1947 at Princeton University (so if you’ve been looking for a way to connect Mark Goodson to Russell Crowe, now you see it), and was first published under the name Hex by Parker Brothers in 1952. Hex is played by two players, represented by two colors, on an 11-by-11 array of hexagons. The goal of each player is to connect two opposite sides of the board with stones of his or her own color before their opponent does. One of the many interesting things about the Hex game is its design: the board never allows for a tie game. The only way a Hex player can completely block his or her opponent from making a connection is by making a connection of their own. This design made for intriguing games as players raced to snake their way around their opponents and go for a winning line.

One of the problems with Hex, however, lied in its even-sided grid. When all of the grid’s sides are of equal length, the first player has a distinct mathematical advantage. Therefore, the pie rule is put into effect, wherein the second player, after seeing the first player’s move, can elect to change sides with his or her opponent for that game and accept player one’s move as his or her own. As Wikipedia so eloquently puts it:

“Since Hex is a finite, perfect information game that cannot end in a tie, either the first or second player must possess a winning strategy. Note that an extra move for either player in any position can only improve that player’s position. Therefore, if the second player has a winning strategy, the first player could “steal” it by making an irrelevant move, and then follow the second player’s strategy. If the strategy ever called for moving on the square already chosen, the first player can then make another arbitrary move. This ensures a first player win.”

Mr. Ryan solved this problem in two ways. First, he resized the board (now consisting of hexagons filled in with letters of the alphabet) so that the game was played with five columns of four hexagons each. Now, since a board with uneven sides theoretically gave the second player the aforementioned advantage the first player would have had, he added an interesting handicap to the game: a two-player team would play against one solo player. The duo would be tasked with completing the longer connecting path, since there were two brains on that side and only one on the opposing side. Blockbusters was born.

In Blockbusters, each initial in each hexagon represented the one-word answer to a question. Contestants were required to buzz in and provide the correct answer in each hexagon in order to claim it. The first team to connect the top of the board to the bottom, or one side to the other, was declared the winner of that game in the best two out of three match and $250. In the Blockbusters pilot, however, there existed a few extra wrinkles, one of them being the mid-show Shortcut To Victory bonus game. In the Shortcut To Victory, the tea that won game 1 was asked to solve three multiple-initial clues (Puzzlers, another 1980 Goodson-Todman pilot created by Steve Ryan, utilized the same concept in its Photo Finish endgame). Completing the set of clues counted as a game two win, which meant that the team advanced to the Gold Rush bonus round right then and there. If unsuccessful, however, the team would then have to play another game of Blockbusters to earn the right to play the Gold Rush.

In the Gold Rush bonus, the board was filled with sets of multiple letters (GWTW, for instance, might require the answer Gone With The Wind). With 60 seconds on the clock, a representative from the winning team would have to make a successful side-to-side connection by selecting hexagons and answering their corresponding questions. The right side of the Gold Rush board was separated into four sections; a successful connection received whatever hidden cash award was hiding behind the section their winning line ended with, up to $10,000.

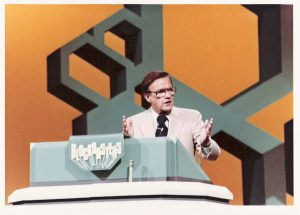

On October 27, 1980, Blockbusters premiered on the NBC daytime schedule. Behind the host podium was Bill Cullen, a man who, in the world of game shows, needs no introduction (but if you do, buy this book). Uncle Bill (as he was known among lots of his fans at that point in his storied career) presided with humor, strong wit, and relative looseness over a game that was very much simplified since the pilot stage. Gone was the Shortcut round, as well as the pick-a-box element in the Gold Rush; instead, the winner of the first game played Gold Rush for $2,500, then for $5,000 after their second win. Later in the series, the format switched to an even simpler best two out of three match, with a game win awarding $500 and a match win redeemable for a shot at the $5,000 bonus game, now called the Gold Run. Thousands of dollars were won as Blockbusters set out to find out “if two heads really are better than one.”

The set of Blockbusters was state-of-the-art for its time. The players’ signaling devices emitted futuristic synthesized tones that totally didn’t match the rhythmic Bob Cobert funk piece that served as the show’s theme song. Bill’s podium would, at the push of a button, sprout a smaller lectern, complete with microphone, for the Gold Run player to stand behind. Of course, the board had come a long way since Hex’s colored stones. The nearly 20-foot-high piece of machinery consisted of 20 hexagonal rear-projection screens, which concealed 20 separate Vismo projectors. Each projector contained slides for the hexagon’s appropriate letter, the red and white colors, the multiple-letter Gold Run slide, and a yellow color for the Gold Run markers. The entire board was flanked by two white fins that would swing in to provide the team of two (referred to on the show as the “family pair”, since the team almost always consisted of two relatives) with the proper connecting color for each side of the board. The fins would

The set of Blockbusters was state-of-the-art for its time. The players’ signaling devices emitted futuristic synthesized tones that totally didn’t match the rhythmic Bob Cobert funk piece that served as the show’s theme song. Bill’s podium would, at the push of a button, sprout a smaller lectern, complete with microphone, for the Gold Run player to stand behind. Of course, the board had come a long way since Hex’s colored stones. The nearly 20-foot-high piece of machinery consisted of 20 hexagonal rear-projection screens, which concealed 20 separate Vismo projectors. Each projector contained slides for the hexagon’s appropriate letter, the red and white colors, the multiple-letter Gold Run slide, and a yellow color for the Gold Run markers. The entire board was flanked by two white fins that would swing in to provide the team of two (referred to on the show as the “family pair”, since the team almost always consisted of two relatives) with the proper connecting color for each side of the board. The fins would  also swing out to reveal the gold sidebars that needed to be connected in the Gold Run. During the show, stagehands were stationed inside the board with the task of shuffling the letters for each main game, as well as replacing the used Gold Run slides and attending to any technical malfunctions that are bound to occur when one is operating 20 slide projectors in close quarters at the same time.

also swing out to reveal the gold sidebars that needed to be connected in the Gold Run. During the show, stagehands were stationed inside the board with the task of shuffling the letters for each main game, as well as replacing the used Gold Run slides and attending to any technical malfunctions that are bound to occur when one is operating 20 slide projectors in close quarters at the same time.

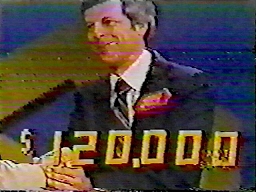

From the outset, the producers instituted on Blockbusters a ten-game win limit, meaning that a player could, at the most, win ten matches and play ten Gold Runs, winning a theoretical maximum of $60,000. Several great players came very close to that threshold during their runs on the show, but one player shattered that glass ceiling despite otherwise unthinkable bad fortune. John Hatten (who had previously appeared on the  ABC quiz show Split Second) won six matches and bonus rounds to the tune of $36,000. During that last taping, however, his California home had burned to the ground. John’s family, who was thankfully unhurt in the fire, knew what had happened and sat in the studio audience, keeping the news from John for fear that it would throw his game off. Despite Goodson-Todman’s offer for him to go home, assess things and come back to the show later, John stayed and played, eventually reaching the maximum $60,000 takeaway. A year later, when Blockbusters upped their win limit to 20 and began inviting old champions back for another shot at the big board, Hatten returned and took NBC for yet another 60 grand, bringing his total to the maximum of $120,000 and making him the biggest solo winner in Blockbusters history.

ABC quiz show Split Second) won six matches and bonus rounds to the tune of $36,000. During that last taping, however, his California home had burned to the ground. John’s family, who was thankfully unhurt in the fire, knew what had happened and sat in the studio audience, keeping the news from John for fear that it would throw his game off. Despite Goodson-Todman’s offer for him to go home, assess things and come back to the show later, John stayed and played, eventually reaching the maximum $60,000 takeaway. A year later, when Blockbusters upped their win limit to 20 and began inviting old champions back for another shot at the big board, Hatten returned and took NBC for yet another 60 grand, bringing his total to the maximum of $120,000 and making him the biggest solo winner in Blockbusters history.

In 1982, ratings for Blockbusters began to sink. Desperate for an answer as to what was wrong with their show, NBC hired a focus group to take a look at the show and hopefully identify a problem. Typically, when a show like this is subjected to a focus group, the conclusion has something to do with the host not being likable, or the game being too hard, or the contestants not fun enough, or the show just not being engaging as a whole. As a result of the Blockbusters focus group, it was concluded that the game itself was engaging and fun to play along with, the questions were interesting and easy enough for early morning viewing, Bill Cullen was a great host, the contestants were easy to root for, the music was awesome, the prizes were great…seriously, nothing was wrong with Blockbusters. For whatever reason, people just stopped watching. And with that, on April 23, 1982, Bill Cullen closed up shop on Blockbusters, but not before relaying some interesting information regarding the success of the “two heads are better than one” handicap. From Blockbusters’ premiere to its finale:

In 1982, ratings for Blockbusters began to sink. Desperate for an answer as to what was wrong with their show, NBC hired a focus group to take a look at the show and hopefully identify a problem. Typically, when a show like this is subjected to a focus group, the conclusion has something to do with the host not being likable, or the game being too hard, or the contestants not fun enough, or the show just not being engaging as a whole. As a result of the Blockbusters focus group, it was concluded that the game itself was engaging and fun to play along with, the questions were interesting and easy enough for early morning viewing, Bill Cullen was a great host, the contestants were easy to root for, the music was awesome, the prizes were great…seriously, nothing was wrong with Blockbusters. For whatever reason, people just stopped watching. And with that, on April 23, 1982, Bill Cullen closed up shop on Blockbusters, but not before relaying some interesting information regarding the success of the “two heads are better than one” handicap. From Blockbusters’ premiere to its finale:

- 37 solo players played 175 Gold Runs and won $806,000

- 45 family pairs played 175 Gold Runs and won $767,000

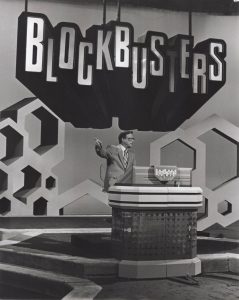

The format appeared again on NBC for four months in 1987. Hosted by the late Bill Rafferty and featuring one-on-one contestants playing on a computer-generated board created by Entec Systems, the show stayed true to the classic Blockbusters format, although the 4 vs. 5 playing advantage switched back and forth between the two players from one game to the next. Tiebreaker games were played on a 4-by-4 grid, meaning that the player who answered the first question correctly in that game also inherited Hex’s old mathematical advantage. It has been speculated, but not proven, that this run of Blockbusters was only meant as a placeholder until Goodson’s Classic Concentration was ready to air. Interestingly enough, during his final few weeks, Bill Rafferty announced Classic Concentration contestant calls right in the middle of Blockbusters episodes.

While only gracing our screens for a little less than two years, Blockbusters fared rather well in other countries, where the game’s contestants were usually children and teenagers from area high schools. Germany and Australia aired their own adaptations of the format in the 80s and 90s. By far, however, the most popular version of Blockbusters aired in the UK from 1983 to 1995, then various reboots in 1997, 2000, and most recently on Challenge TV in 2012 hosted by Simon Mayo. British Blockbusters is regarded as one of the most beloved game shows in the history of UK television, and has even spawned its own catchphrases; “I’d like a P, please”, uttered when a contestant selected that letter off

the board, is easily the most recognizable to British game show fans. In Dubai, reruns of the UK series were so popular for many years that shops around the country closed for business while the show was on. Dubai also hosted live annual Blockbusters tournaments sponsored by Gulf News for many years, for which they flew in original UK host Bob Holness to serve as emcee.

Cathi Ryan, Steve’s wife, poses with some of his game show memorabilia, including the Blockbusters home game, logo from the front of Bill Cullen’s podium, and the preserved slate from the final taping

Blockbusters is proof that, sometimes, a good game just doesn’t get a fair shake. For whatever reason the game never made a winning connection with the audience, game show fans–and creator Steve Ryan, who remains active in the game and puzzle community and on Facebook–can take solace in the knowledge that this wonderful game has captivated generations of game players and is fondly remembered the world over.