#tbt: Jeopardy! on NBC

In this edition of Throwback Thursday, Christian Carrion explores the early years of the most iconic quiz show in TV history.

It’s been quite an exciting week for the Jeopardy! crew. This past Sunday, the syndicated quiz institution celebrated an enormous milestone—its 14th Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Game Show. Jeopardy! now has a total of 31 Emmys under its belt and continues to be recognized by Guinness as the winningest game show in television history. In addition, host Alex Trebek earned himself a world record by becoming the presenter who’s hosted more episodes of the same game show than any other.

It’s been quite an exciting week for the Jeopardy! crew. This past Sunday, the syndicated quiz institution celebrated an enormous milestone—its 14th Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Game Show. Jeopardy! now has a total of 31 Emmys under its belt and continues to be recognized by Guinness as the winningest game show in television history. In addition, host Alex Trebek earned himself a world record by becoming the presenter who’s hosted more episodes of the same game show than any other.

These commemorations, however, are but a drop in the gilded bucket for Jeopardy!, a program whose longevity, intrigue, and commitment to a tried-and-true formula have made it a favorite among several generations and cemented its place in pop culture. Home versions of the game, digital or not, have been big sellers for decades. Prolific contestants have reached international fame, prestige, and fortune way beyond what they’ve earned at the podium. The show’s signature “Think!” music, originally written by series creator Merv Griffin as a lullaby for his son, has become a musical colloquialism for the concept of thought under pressure. Midterm review sessions captained by fun-loving teachers wielding multicolored index cards (or, more commonly these days, one of umpteen PowerPoint presentations) serve as irrefutable proof of the educational value this brilliant game holds for students of all ages.

Get a bunch of those students in a room and ask them who the host of Jeopardy! is, and you’re fairly certain to get the same answer throughout. If you’re really lucky, one of those kids might just tell you it’s “that guy with the mustache.” It’s true that just about every American aged 30 and under these days has never known television without Jeopardy!, but they’ve also never known Jeopardy! without Alex Trebek. What’s even more interesting is that there exists a generation of young people who have no idea that the game they watch with their families around dinnertime during the week is, in fact, older than some of their parents. You see, half a century ago—back when Alex was a 24-year-old up-and-coming broadcaster, and a decade before Ken Jennings was even in the form of a question—America’s most popular quiz show resided in daytime on NBC.

It can be said that Jeopardy! was one of the more positive by-products of the quiz show scandals that plagued the late 1950s. The era of sponsor-driven, high-pressure, big-money quizzes in which the beautiful people were “blessed” with all the answers came to a head near the end of the decade, when a number of whistleblower ex-contestants came forward and exposed the rigging that had been going on behind the scenes—and before viewers’ eyes—for years. Americans felt duped, networks were furious, and the reputations of many contestants and producers were ruined. The game show genre was dealt a crushing blow from which many thought it would never recover.

Therefore, imagine the surprise Merv Griffin felt when, on a plane ride from Duluth to Los Angeles, his then-wife Julann suggested he make a game where all the players were given the answers. Griffin, who had hosted game shows like Play Your Hunch and Word For Word, was itching to set out on his own and produce a game show himself. As can be imagined, however, his desire to create a new show outweighed his desire to go to prison, and he immediately dismissed Julann’s idea.

“No, no,” Julann said. “Look. Five thousand, two hundred eighty.”

Merv thought for a second. “How many feet are in a mile?”

The idea clicked instantly. The contestants would all see the answer, and the challenge would be in coming up with the question that fit the answer. Griffin started work on his new game show at once. He came up with the idea of a game board containing various answers in several categories which escalated in difficulty and dollar value. For several days, Merv invited friends to the dining room of his New York City apartment to help him flesh out the game.

The first prototype of the new show had the working title What’s The Question? and called for a board with ten categories, each containing ten answers. The concept was scrapped, however, when it was discovered that the enormous board would jut out into the audience area in the studio at Radio City Music Hall where the pilot was to be taped. Griffin went back to the drawing board (no pun intended) and shrunk the game down to two six-category rounds of increasing difficulty, with each category consisting of five answers each. He presented the revamped idea to NBC, who loved the game and agreed to air it without any need to make a pilot episode. Network executive Ed Vane, however, didn’t see it as a particularly exciting game. Years later, Monty Hall would say that a good game show contains one or more moments wherein a contestant could either win everything or lose everything; Mr. Vane’s problem was that there were no such elements of risk in Merv’s quiz game. “It needs more jeopardies,” he said. “There aren’t enough jeopardies.”

Jeopardy. Jeopardy! What a word!

Merv didn’t hear anything else that was said in that pitch meeting. He went back to his staff and announced that their new show was no longer called What’s The Question? The game show’s new title was Jeopardy!

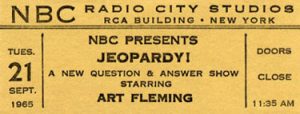

Phase 1 of the plan to add more risk to Jeopardy! was the addition of a betting element. Griffin decided that one or two of the thirty clues on the board in each round would enable the contestant who selected it to wager any or all of their winnings up to that point in the game. This new mechanic was called the Daily Double, a name that NBC initially didn’t like for fear of its connotation with gambling and horse racing. The Daily Double would allow for thrilling big-money victories by exceptional players, as well as for second- or third-place contestants to make a last-minute dash for the lead. Phase 2 was Final Jeopardy!, an end game in which all three players would write their responses to the same answer. The category was announced beforehand, and contestants were allowed to bet as much money as they desired based solely on their knowledge of that category. Finally, the overarching risk element was that the players stood to lose the dollar value of the answer if they incorrectly questioned it, giving the illusion that this was the first game show where a contestant could end in the negative and owe money (which they didn’t, of course). With the jeopardies in place, the set built in Studio 6A at New York’s Rockefeller Center, and the Julann Griffin-composed big band theme cued up, Jeopardy! premiered at 11:30 AM on March 30, 1964.

Phase 1 of the plan to add more risk to Jeopardy! was the addition of a betting element. Griffin decided that one or two of the thirty clues on the board in each round would enable the contestant who selected it to wager any or all of their winnings up to that point in the game. This new mechanic was called the Daily Double, a name that NBC initially didn’t like for fear of its connotation with gambling and horse racing. The Daily Double would allow for thrilling big-money victories by exceptional players, as well as for second- or third-place contestants to make a last-minute dash for the lead. Phase 2 was Final Jeopardy!, an end game in which all three players would write their responses to the same answer. The category was announced beforehand, and contestants were allowed to bet as much money as they desired based solely on their knowledge of that category. Finally, the overarching risk element was that the players stood to lose the dollar value of the answer if they incorrectly questioned it, giving the illusion that this was the first game show where a contestant could end in the negative and owe money (which they didn’t, of course). With the jeopardies in place, the set built in Studio 6A at New York’s Rockefeller Center, and the Julann Griffin-composed big band theme cued up, Jeopardy! premiered at 11:30 AM on March 30, 1964.

Art Fleming, a tall, handsome actor, was the original host of the show. Fleming, a native New Yorker, had spent the past few years playing various roles in television dramas, including a stint as attorney Jeremy Pitt in the NBC Western series The Californians. Art was also the original voice in the famous commercials that told viewers “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should.” Merv Griffin invited Fleming to audition after spotting him in a television commercial for Trans World Airlines and finding him to be “authoritative, yet warm and interesting.” That was indeed the spirit of his presence as host of Jeopardy!: he opened every episode with a warm wave and a greeting to the day’s players, to the viewers in the studio and at home, and to announcer Don Pardo. In addition, his clear, booming voice was perfect for such a reading-intensive show; viewers were treated to Art’s dulcet tones as the answer, usually riddled with abbreviations to allow it to fit in the box, appeared on viewers’ screens.

Art Fleming, a tall, handsome actor, was the original host of the show. Fleming, a native New Yorker, had spent the past few years playing various roles in television dramas, including a stint as attorney Jeremy Pitt in the NBC Western series The Californians. Art was also the original voice in the famous commercials that told viewers “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should.” Merv Griffin invited Fleming to audition after spotting him in a television commercial for Trans World Airlines and finding him to be “authoritative, yet warm and interesting.” That was indeed the spirit of his presence as host of Jeopardy!: he opened every episode with a warm wave and a greeting to the day’s players, to the viewers in the studio and at home, and to announcer Don Pardo. In addition, his clear, booming voice was perfect for such a reading-intensive show; viewers were treated to Art’s dulcet tones as the answer, usually riddled with abbreviations to allow it to fit in the box, appeared on viewers’ screens.

Jeopardy! in the 60s was played much the same as it is today, although there was a lot less money involved; the first round’s answers were valued at $10-$50, and those amounts were doubled in Double Jeopardy. Also noticeably different from its modern-day counterpart is the difficulty and nature of the game material. Many of the answers from the first couple of years were usually very terse, requiring more than a simple prefix of “What is” or “Who is” attached to the correct response (for example, the answer ‘X’ in a Sports category might require the question, ‘What letter denotes a strike in bowling?’). Early on, Griffin thought that requiring correct grammar when questioning an answer (“Who is” for a person’s name, etc.) would add some levity to the proceedings and help the show distance itself from the tainted quiz games of the previous decade, but decided against it when he saw how much it slowed the game down—contestants spent most of their time trying to wrestle their questions into the proper format, and a great deal of game material went unused.

Jeopardy! in the 60s was played much the same as it is today, although there was a lot less money involved; the first round’s answers were valued at $10-$50, and those amounts were doubled in Double Jeopardy. Also noticeably different from its modern-day counterpart is the difficulty and nature of the game material. Many of the answers from the first couple of years were usually very terse, requiring more than a simple prefix of “What is” or “Who is” attached to the correct response (for example, the answer ‘X’ in a Sports category might require the question, ‘What letter denotes a strike in bowling?’). Early on, Griffin thought that requiring correct grammar when questioning an answer (“Who is” for a person’s name, etc.) would add some levity to the proceedings and help the show distance itself from the tainted quiz games of the previous decade, but decided against it when he saw how much it slowed the game down—contestants spent most of their time trying to wrestle their questions into the proper format, and a great deal of game material went unused.

The first-ever Final Jeopardy! category was Famous Quotes. The answer: “‘Good night, sweet prince’ was originally said to him.” The show’s first champion, Mrs. Mary Eubanks from Candor, North Carolina, won $345 on that premiere broadcast with her correct question, “Who is Hamlet?” Nobody else walked away empty-handed, however—back then, all Jeopardy! contestants kept the money they earned throughout the game, win or lose.

Contestant selection for the first version of Jeopardy! involved visiting the show’s New York office, taking a test, and then waiting for up to six weeks while the people in charge sorted through the hopefuls and made some phone calls. Merv Griffin explained the early trials and tribulations of casting for the show in the 1990’s The Jeopardy! Book:

Our first contestant coordinator was a summer-stock director from Norfolk, Virginia, who had been an acting coach for my wife and for Gene Wilder. I figured if he could develop young acting talent, he would be able to spot good contestants. The problem was that he assumed all the smart people in New York lived in Greenwich Village, so in the first few months of the show a disproportionate number of contestants arrived with brooding expressions, dark capes swung over their shoulders, and books of poetry protruding from their pockets. People from the Midwest thought we were subsidizing every Marxist intellectual in the country. So we tried another contestant coordinator, and began to find contestants who were both smart and personable.

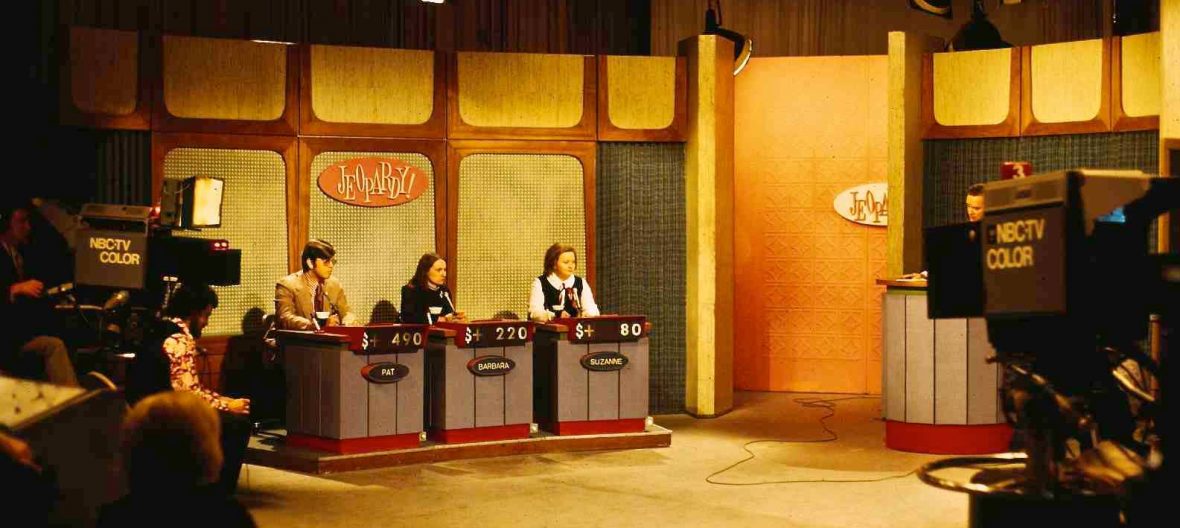

The Jeopardy! game board from behind, as seen by the stagehands

The set for the original Jeopardy! was essentially a mirror image of the present-day version. At the top of the show, Don Pardo announced the contestants by name as, one by one, they walked stage right, had a seat at their podiums, and pulled themselves in with their chair as if to sit down to a big meal. Host Art Fleming would take his place behind a podium that sat in front of an aqua-blue curtain; the unchanging shot of Art in front of that backdrop was almost medicinal to the millions of people who made watching Jeopardy! a daily habit, in much the same way Bob Barker’s backdrop on The Price Is Right remained unchanged for so long. The contestants faced a board consisting of 30 pull-cards operated backstage by two stagehands. When a box was selected, a stagehand would pull the dollar amount out from behind the board, revealing the answer. This was usually done quite vigorously—the deafening slam the cards made as they were yanked from their holders often startled unsuspecting audience members. Scores were tallied on each contestants’ podium using large mechanical devices not unlike those seen above old-fashioned skyscraper elevators to denote the floor the car was on.

Bill Cullen of Three On A Match, Peter Marshall of The Hollywood Squares, and Art James of The Who What Or Where Game play a special celebrity Jeopardy! match in 1972

Jeopardy! was popular with viewers from day one, and by the end of the decade, it was second only to NBC’s The Hollywood Squares as the most-watched daytime game show on television. In that time, several present-day Jeopardy! mainstays debuted in their original forms. An annual Tournament of Champions sought to crown the best player from the previous year’s broadcasts; Count Of Monte Cristo screenplay writer and game show producer Jay Wolpert took the title in 1969. College and high school students were invited to play in special tournaments, the winners receiving scholarship money. Episodes with celebrity contestants were also fan favorites; movie critic Gene Shalit and iconic game show host Bill Cullen, among others, were seen playing America’s new favorite answer-and-question game for the charities of their choice.

Mel Brooks (right) as the 2,000-Year-Old Man, greeting Burns Cameron on episode #2000

In 1972, Jeopardy! celebrated its 2,000th broadcast. In honor of the event, the three highest-winning contestants returned to play a charity game in which one Daily Double resided in each category (one of those contestants, Burns Cameron, went on to play in the $250,000 Super Jeopardy! tournament on ABC in 1990). In addition, Mel Brooks, a devoted viewer of the show, made a rare walk-on appearance as the 2,000-Year-Old Man. The special episode closed, quite appropriately, with the credits rolling as the theme song from the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey played.

Art Fleming and contestants on the nighttime syndicated Jeopardy, 1974

Jeopardy’s ratings held up until 1974, when new vice-president of NBC daytime programming Lin Bolen moved the show to 9am from its longtime noon time slot in an effort to re-energize the 18-34 female demographic. In its place came louder, flashier shows featuring handsome hunky hosts—Geoff Edwards’ Jackpot and Jim MacKrell’s Celebrity Sweepstakes, to name a few. Around this time, however, Jeopardy! had expanded to a nighttime syndicated edition. Not too much had changed from day to night, other than a bit more glitz on the set and Art Fleming in some of the ugliest tuxedos man has ever encountered. A bonus game played by the winner of each episode gave the champ the chance to drive away in a new Chevrolet Vega if he or she picked the lucky space on the game board. In the daytime, however, Jeopardy! had begun to drown, and it seemed as if there were no life preservers in sight. Ratings continued to drop until January of 1975, when Art Fleming and the daytime crew said their final goodbyes; the nighttime version got the ax soon after. Another Merv Griffin-created game, Wheel Of Fortune hosted by hunky Chuck Woolery, premiered the following Monday.

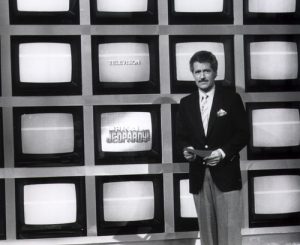

Alex Trebek on the new, modern Jeopardy! set

While announcer Don Pardo moved on to bigger and better things in the form of a new variety show called Saturday Night Live, Art Fleming, who never missed an episode in the 11 years Jeopardy! was on NBC, never found a project that matched the success of the answer-and-question game. A brief revival on NBC in the late 70s with slightly altered rules and a new $5,000 bonus game proved unsuccessful and was off the air within five months. Art also made cameo appearances in the film Airplane II: The Sequel, as well as in the video for the “Weird” Al Yankovic hit I Lost On Jeopardy. In 1984, Merv Griffin approached Fleming with the opportunity to host the new syndicated Jeopardy!, but he declined, thereby leaving Merv to hire Alex Trebek. In the years after its premiere, Art largely approved of the new show, but voiced his displeasure with the rule that stated only the champion got to keep his or her cash winnings; nevertheless, Alex’s Jeopardy! carried on and became a hit with viewers all over again. Art hosted a daily radio show on KMOX-FM in St. Louis, Missouri from 1979 until 1992, as well as a syndicated program called When Radio Was. Art Fleming passed away of pancreatic cancer on April 25, 1995 in Crystal River, Florida. A studio at NBC in Burbank was named in his honor.

In an industry where half-baked concepts are hashed out over and over again to a weary viewing public, Merv Griffin’s game of trivia with a twist stands in a league of its own. The original Jeopardy! was a tree that grew in Manhattan, among the steel and the concrete of 30 Rock, with all its glorious leaves and branches. One day in the early 80s, it passed on its legacy through the seeds it dropped to the ground, and as the wind carried one fortunate seed through the lavish Holllywood air, a new life began for this, the soon-to-be most awarded game show of all time, as it now stands as a monument to the one that came before.

Tell Us About Yourself

Tell Us About Yourself The Lost Carmen Sandiego

The Lost Carmen Sandiego