What Is The Best Video Game Adaptation of a Game Show?

A delusional Cory Anotado makes a bold claim to the title of Best Game Show Video Game.

Game show video games are an interesting part of the art form. Since the Atari era, publishers have attempted numerous translations of games that are already on television to make them fully interactive experiences. Early successful ports include the various Wheel of Fortune computer games, most notably the ugly four-color EGA versions with a Wheel layout generously described as “inspired by someone who watched the show once;” and Rare’s (yes, the Banjo-Kazooie, Goldeneye, Conker’s Bad Fur Day Rare) myriad efforts to bring Jeopardy! to the Nintendo Entertainment System. Even today, Wheel of Fortune’s Nintendo Switch version has a wide audience of fans—personally, I can attest to this, as I organized a wait-listed tournament of the game at last year’s MagFEST conference. (A landing on Bankrupt elicited a louder outcry than the Street Fighter tournament happening across from us at the same time.)

The spectrum of game show video games ranges from the absolute dreck (see Deal or No Deal or the Nintendo DS) to top-tier adaptations (both Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune for the Nintendo Wii).

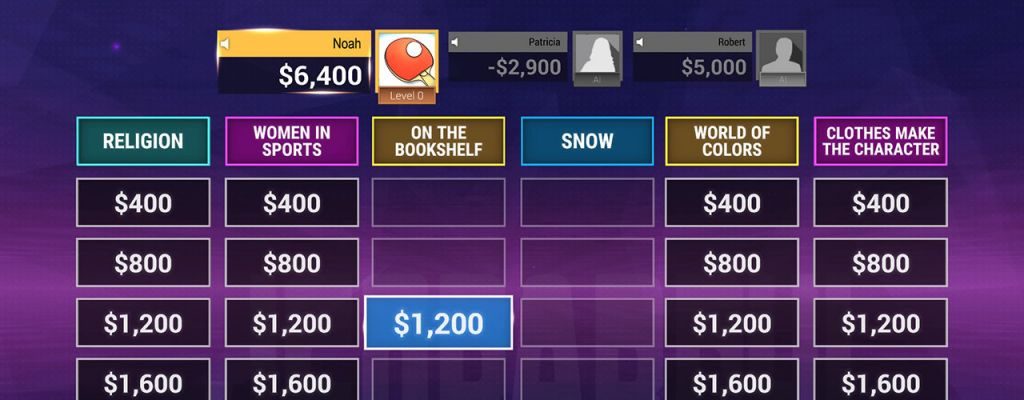

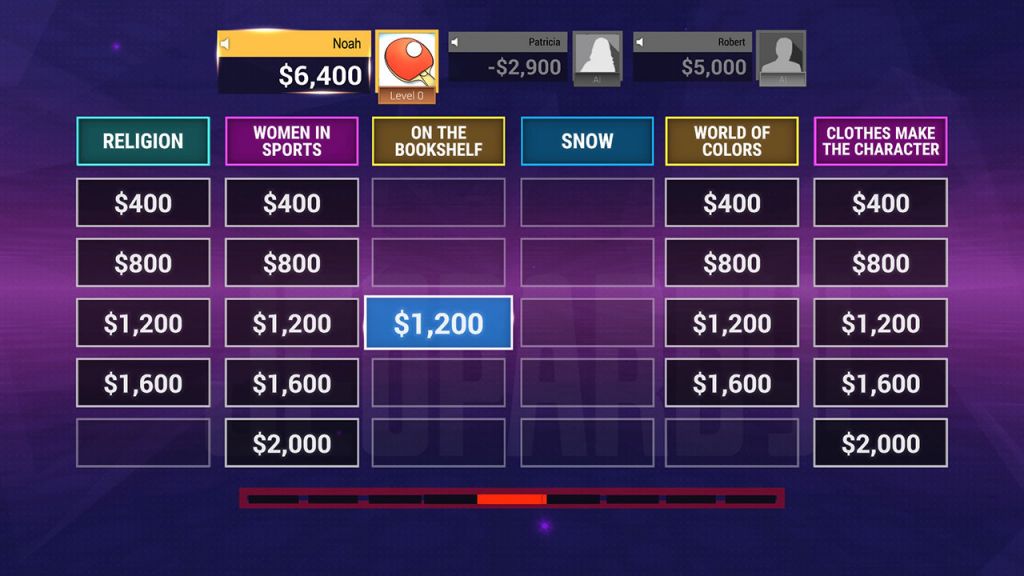

What makes a good game show video game? It has to maintain a fine balance between being fun to play at home while still maintaining the television magic of the game show it’s simulating. Take, for example, Jeopardy! for the Nintendo Switch. For most casual gamers, Jeopardy! on Switch is probably a fine adaptation. It has all the trappings that you’d expect from a game of Jeopardy!: categories, clues in the form of a question, Daily Doubles, and Final Jeopardy!.

But even passive viewers of Jeopardy! may find that the game doesn’t pass the sniff test of authenticity. The issue with it is that it doesn’t feel like Jeopardy!. There is no set, there are no podiums, there is no host reading out clues; the main Jeopardy! theme appears only once: when you first boot up the game. Half of the fun of game shows is the rigamarole: the lights, the announcer, the music. The little trappings that feel like your favorite television show are important. When they get removed, it’s disappointing. Wheel of Fortune for the Switch gets a lot more right, with an accurate model of the famed Wheel of Fortune set, even if Pat and Vanna are replaced by generic replicants who could go rogue and destroy everything at a moment’s notice.

Now, making a good video game isn’t easy. You have to leverage the hardware you’re targeting, making sure that the game controls nicely and intuitively, looks clear and concise on whatever display the system has, and has enough replay value to justify the price tag. You also have to adapt the game show you’re making to be a video game—taking the essence of the show and making it friendly for someone who’s on a couch with their friends. It also has to flow about as seamlessly as the shows on TV tend to flow. Inputting words or phrases needs to be assisted by a good auto-correct algorithm or an excellent parser backed by an extensive dictionary.

So, what then, is the best video game adaptation of all time? It’s a loaded question, and I could make the case for a variety of different answers. The Wii version of Wheel of Fortune ranks up as one of the most feature-complete game show video games on the market, as it includes full speech clips from both Pat and Vanna, and Charlie O’Donnell (RIP), but thousands of puzzles, Wii Speak and Mii support, mini-games for parties, lots of unlockables and replay value for miles and miles. The Chase Ultimate by Barnstorm Games for seemingly every device that can run Unity (including the brand new Nintendo Switch version) is also feature-complete, with updates to include every single Chaser from the UK version, host quips from Bradley Walsh, hundreds of questions and the ability to filter questions into categories like TV and Movies or Sport, and a special Chaser mode where one player can actually be the Chaser. Put the icing on the cake of the official Chase soundtrack in the game, as well as show-accurate typefaces and graphical elements, and The Chase Ultimate lives up to its name.

I will also give special callout to the Nintendo DS version of Jeopardy!, which not only has many of the same elements as the Wii version from which it derives, but the light pen feature to write your name works exactly like the one on the Jeopardy! set (and I should know). It’s also one of the rare modern Jeopardy! video games that allow you to actually type in your Final Jeopardy! response from scratch, unlike the Wii version that makes you choose from multiple choices.

But today, I’m going to suggest a game that I return to over and over again. It’s a faithful adaptation of the show it’s emulating, but in a form factor that carries not only the atmosphere of the game show but its own charm, while still providing a considerable challenge. What game is this?

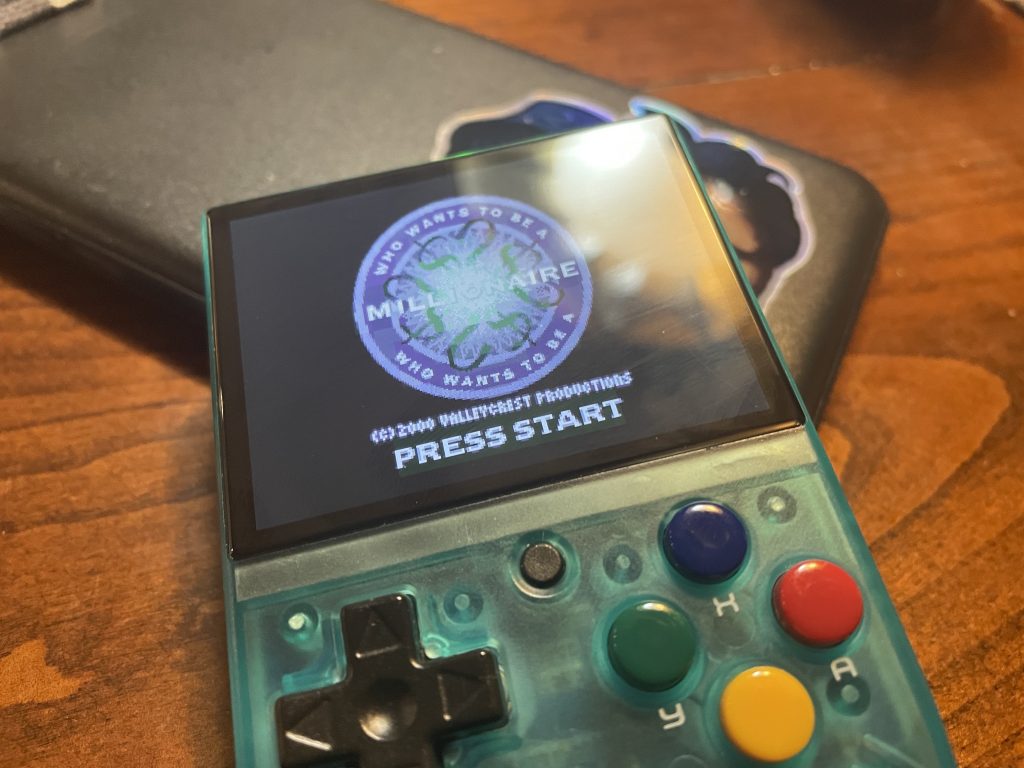

Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, 2nd Edition, for the Game Boy Color.

No, wait. Don’t click away. Hear me out.

Who Wants to be a Millionaire? for the Game Boy Color is a port of the excellent WWTBAM? PC game originally developed by Jellyvision (now Jackbox Games). Taking the je ne sais quoi of their You Don’t Know Jack games and combining it with the national sensation of Millionaire (and getting Regis in the booth to be Regis) was a winning combination. The Game Boy Color port shrunk down that PC game into a simple yet effective port that still holds up today.

It helps that the gameplay of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? is extremely simplistic: 15 questions to get to $1,000,000. Safe havens at the $1,000 and $32,000 levels exist. All three lifelines are included, including the Phone-a-Friend, which has been translated into scrolling text on the bottom of the screen. What makes the GBC version of the game a joy to play to this day is its speed. Without the interspersed comments from Regis, the game can easily be a 5-10 minute affair to get to the million dollar question.

That’s the point, though, since it’s on a handheld system that, at the console’s inception, was built to play in short bursts. Type in your name, a pre-rendered zooming-in of the Hot Seat plays, and you’re in the game. The art style is sparse, but that’s not unlike the PC version or even the show itself. The trivia itself stands up well for being a game that is 23 years old. Some questions show their age (for instance, asking what the K stood for in Y2K) and some may soon be incorrect (like asking about the college that produced the most Heisman winners) but by and large, the game, which ported over seemingly every question from the PC game, has trivia that almost feels timeless. The fact that I can still play this game today, easily, makes it stand up over the PC version from which its based (which if I want to play today means I’ll need to plug in my classic iMac G3).

One of the shining features of the game is the music, a shockingly faithful translation of parts of the Who Wants to be a Millionaire soundtrack done in a chip tune style by Jakob Kaufmann and Paul Bragiel. Listen to this arrangement of the first five questions’ background music:

Even though I’ve played dozens of games of this, I rarely see any repeats, and some questions give me a lot of pause. Winning the top prize is still exciting and rewarding. For a game labeled “2nd Edition” that had neither a first or third edition, the Game Boy Color version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? still stands out today as one of the most fun, pure game show ports I’ve ever played. Whenever I acquire a device capable of playing Game Boy Color games, like my recently-purchased Miyoo Mini, I make sure that I have a copy of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? for Game Boy Color ready to play.

And that’s my final answer.