Prolific Composer Edd Kalehoff Shares The Secrets Behind Your Favorite Game Show Themes

Christian Carrion talks with the iconic game show theme composer and synthesizer virtuoso, ahead of the release of his new album.

In the realm of television music, there are a select few individuals who have managed to leave an indelible mark on our collective auditory memory. One such maestro is Edd Kalehoff, a name synonymous with captivating melodies that have set the tone for countless beloved TV shows. Whether it’s the infectious rhythms of game shows like The Price is Right or Trivia Trap, or the energetic pulse of ABC’s Wide World of Sports, Kalehoff’s distinctive musical fingerprints can be found on some of the most memorable TV moments of all time.

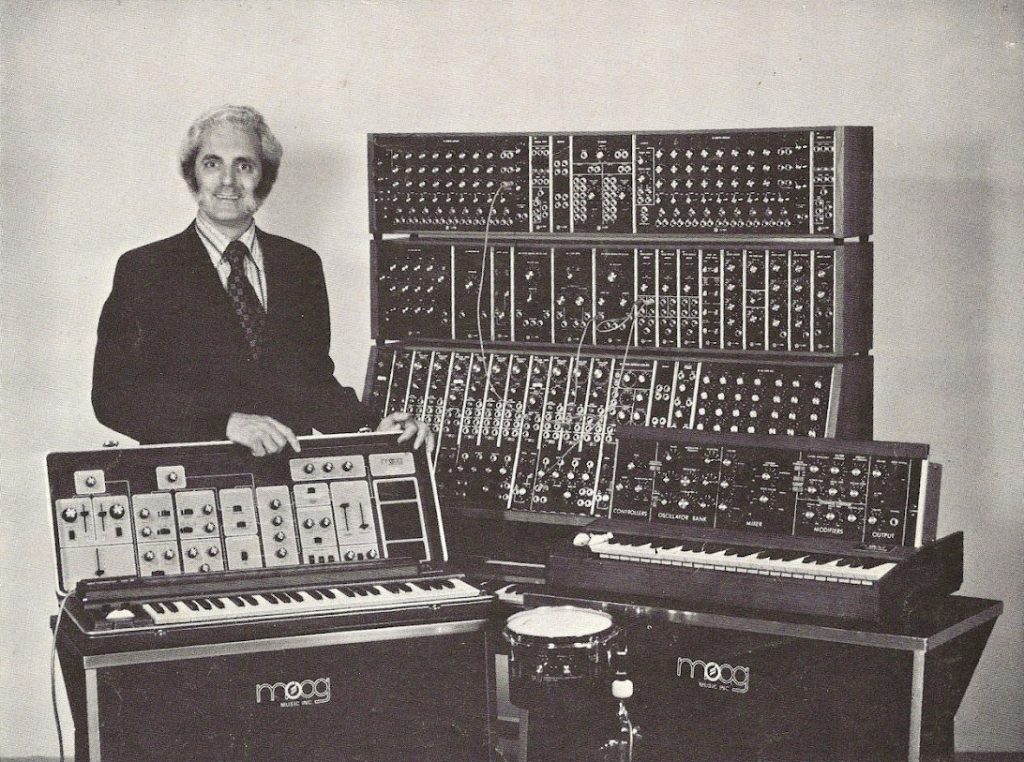

This year, after over half a century of composing television production music, Edd Kalehoff is releasing his very first album. Moog Grooves (Sifted Sand Records) is a compilation of never-before-heard synthesizer productions recorded from 1971 to 1979, the heyday of the Moog-synth game show theme. In celebration of this upcoming release, I had the pleasure of speaking with Mr. Kalehoff about a wide range of subjects for an interview that spans much of his illustrious career, and then some.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I read that your father played piano in the White House for a couple of presidents. Is that true?

Yes, it is. Well, he actually had had an a couple of Hammond organs. And he even had one of his Hammonds on the Joint Chiefs of Staff warship to play for the parties. When, when they would meet, they would never tell him where he was going. And, of course, Margaret Truman loved to sing and so he was the official organist of the White House. You know, crazy stuff.

That’s amazing. And so music, and keyboard in general, runs in the family.

Yeah. I actually have one of his Hammonds. Which is… it’s like a B3. Well, the big models were B3 and C3. The B3 was the nightclub model with the open legs, and the C3 was the chapel or church model with little carvings on the side, you know, nice little inlays.

And I have a C3 and played a lot of saloons and nightclubs on my way up to you know, getting a degree and starting writing for serious work, you know, and being a composer. But I actually was playing the Hammond, the one I bought years ago, on Sunday. I was playing it with my my grandson who’s learning how to do the pedals, learning about the Hammond.

But that starts with my dad. And he also was a very accomplished pipe organist. There was a big one in Philadelphia, the John Wanamaker big pipe organ. He played that a lot. And so it was I was exposed to the big sounds of a real king of instruments, the pipe organ. And a lot of my friends, as I produced music throughout the years said, “Man, you know, hearing those 32 foot pipe organs that can shake the, you know, the stone churches and the cathedrals really made me appreciate the bottom end.” You know, a very hefty bass.

And I still like a good subwoofer and fill it up, you know, with great basslines and great players. But, you know, I think it all came from being a kid, not knowing what I was listening to, but just, you know, having the ground shake. I said, I like that.

And then of course my mother, to give her credit, was the one that said “Edward, did you practice your guitar today? Did you practice your piano? Did you practice your organ playing today?” She was the one that that did that. She was a doctor of sociology, a PhD, and was really influential, you know. So dad did the exposure of the music, and my mother, like, hammered it into me.

And so, growing up with this appreciation of pipe organs, seeing the Moog synthesizer years later, you must have felt like you were on the cutting edge of music. It must have felt like the future.

Absolutely. What happened was, I had my mother in Mississippi, my father in Philadelphia. They were always together, but we would go to Mississippi. I loved it down there. I mean, it was like, you know, horses and cows and Jackson, and the exposure to the music was exceptional. I went to the Philadelphia Musical Academy and took a year off with a jazz choir at the University of Southern Mississippi and went and swept a lot of the jazz festivals with my choir.

And so we had a good run there. I came back to Philadelphia and I was playing the nightclubs around the Philadelphia area, in New Jersey, Cherry Hill, and in the summer coastal cities up and down the East Coast. I was exposed to the Moog and I said, “wow, that’s it.” It harkened back to when I was three years old. I used to drop my trucks. Well, I would hear that. I would drop my little trucks and run and play the piano, you know, and like, be fascinated with…one note, two notes, little fingers and, you know, little songs. I felt the same way when I saw the Moog.

So then I said, “I gotta learn this thing.” You know, cuz it’s pretty, pretty difficult to get the patch chords and know where you’re going with it. We had a little music room—little—they called it the Electronic Music Lab. And the custodian (named Jimmy) that cleaned it up, great guy. Jimmy gave me a key because I would finish playing the mafia clubs, and I would come in at 2:30 in the morning, three o’clock, and I would be able to spend some quality time just playing with this thing. And I walked in one night and I saw a little guy… little, little, little gray-haired guy in a sleeping bag with his little head sticking out. Scared me. I said, “Who are you?” He said, “Well, I’m Bob.” I said, “Bob who?” “Well, I’m Dr. Robert Moog.” So from that moment on, we became best friends. And I said, well, show me what your thing does here. Right? Show me the low pass, high pass filter coupler. Show me that stuff. And I got a crash course from the guy that invented it. I’m still very good friends with his beautiful daughter, Michelle Moog, who has the Moogseum, I think they call it.

I said, “Bob, I’d like to play music on this thing, but it needs a keyboard.” He said, “I can do that.” So he got a little controller together, and instead of a ribbon controller, he had a keyboard. So he kind of attributed me and a few guys with forcing the keyboard thing into the Moog world. And of course, it opened up all kinds of things.

I mean, Bob was…magical. He built my first studio for me, which was I guess early early seventies—you know, we were all young then. And he’d always come to town, and we’d see each other and he would always tune it up (for me).

A lot of the famous composers in Los Angeles opened doors for me, And they’re all great guys. I learned so much from them. We just lost Burt Bacharach, and he influenced me a lot. Phil Ramone, the producer and engineer of so many of those wonderful Bacharach dates…he said, “if you teach me the Moog. I’ll introduce you to the sessions.” I mean, he’s talking about The Carpenters and all of the big recording artists of the sixties and seventies. I mean, even before that.

I loved orchestration, so that opened up Quincy Jones, and Bob James and his keyboard work. And so we did a few movies together and it was an inspired bit of time because I was able to teach Phil the Moog.

They were doing a movie in London. Phil loved to go to London cuz that was the, you know, the, the height of the Beatles and the English invasion. And he was doing it. A John Barry liked a, an orchestra, maybe 90 pieces, huge. And I got a call—they were in London. At like one or two in the morning the phone rings and I’m in New York. He says, “Kalehoff, get on an airplane as soon as you can.” Because Phil was having a hard time getting the thing to tune. They were very difficult to tune, the Moogs.

So I had to quickly, you know, throw my pantyhose in a bag and jump on an airplane and fly to London. That’s how I met John Barry. And they loved the Moog because they could do the beeps and the sequential beats. A lot of it was futuristic and outer space. And…with the white noise and the control of the sound, you could make a great explosive sound, which no one could ever hear before the Moog could do it. And so that was an exciting time…the James Bond movies and making beeps and spaceship sounds and doing some melody work. (Phil Ramone) fell in love with the ability of the Moog to add a sparkling new sound on top of the strings

I came to town to write and not to just play, you know. I would do a couple dates here and there, but once you start getting booked, it takes your time and you have to, like, drop your music and drop your session and go to play someone’s session.

And because of the competitiveness of melody, I’d be in the middle of writing something as a commission piece of work and I’d have to go play someone else’s video. I’d say, “look, I don’t wanna be sued.” So I kind of just stopped doing outside dates and started building studios. I called it my, my bag of tools. You know, I guess I built maybe four or five. Moog built the first one for. Exquisite work. I mean, his potentiometers and the wiring and the way he put things together was unbelievable. And by the way, those modules are still working, and they’re in my studio here in New York. I mean, there’s an electronic instrument. Built in the late sixties. And it still works. You know, you have to clean it now and then, you know, get the dust out.

They don’t build them the way they used to.

No, they don’t. Everything’s now a black box; a disposable thing you just throw away, you know?

In my mind, there is a paradigm shift around the time The Price is Right premiered. We’re talking about the early seventies, because game show music before that point was usually a lot of stock music. It had a big band kind of sound to it, or it sounded kind of hokey. The Price is Right came out and your music package was the score for the show, and it sounded like the future. A lot of game shows going forward, some that you scored and some that you didn’t, had that sound. It did usher in this new era (of music). In your estimation, what was different about your approach to composing television music? What made your music stand out? What did you try to do differently when you set out to compose a score for a television show?

Most of it was for Mark Goodson-Bill Todman Productions. Bill passed away early, much earlier, and Mark kept going and we had a great relationship. And so money was never an object.

He’d say, “I need music,” for a show like Password or TattleTales or Price. And so I would go and study it with him. I like to show up for jobs. I saw some of the old things with Bill Cullen, and it was dry and it was like, you know, Dorothy Kilgallen and Bennett Cerf…you know, the old style of show.

I’d say, “okay, it’s gonna cost you $50,000 for me to go (to London and record the music package), that’s a total price.” And one day I said, “Mark, why don’t you ever question me as to how much it costs?”

He said, “Because you told me that’s how much it costs. I want you to be happy. I don’t want you to go anywhere else, and I want you to do my shows. If that’s what you say it costs, that’s the cost of it. I don’t want anyone else to try to buy you away from me.” I had been exposed to 90 piece orchestras with John Barry. Of course, I didn’t use 90 pieces. You know, we’d go with a chamber group…like maybe 30 guys, strings and brass. Everything was live then.

One thing I like to do is, I like to put the name of the show in the thematic element, whatever it is. You know, so if it’s TattleTales…🎵Tatt-le-taaales, ta-ttle-taaales…🎵

The Price is Right? 🎵The-price-isriiiiight, the-price-isriiiight…🎵

So Mark would tap his foot, and he’d say, you know, “Mark, I can say the name of my show in that melody.” I said, “right.” He would love to try to pick out which part of the melody was the name of his show. It was fun.

I mean, it wasn’t every show we did that. It wasn’t a necessary formula…

I have to stop you for a second and tell you one of the questions I have on my list that I was most apprehensive about asking, because I thought it would sound insane. “Does the title of the show purposely fit into your music?”

(laughs)

Because I have noticed that in the themes that you write, the title goes along with the main melody, and Double Dare is one that sticks in my head in particular. That 🎵Double Dare!🎵, like, it’s to the main melody of the song. I swear to God, I said, “I’m gonna ask this question. I’m gonna sound insane, but I’m gonna ask it anyway.”

No, that’s amazing. Listen, you are hitting the nail on the head. Yes. That’s so much of the inspiration. And it goes into everything I do. You know, if I’m writing the theme for the Super Bowl or for news. It wasn’t a formula, but it would go into every form of writing. Even doing Hank Williams (Jr.), you know, we did his song. It started out as “All My Rowdy Friends”, and then it turned into a big climb, because it was to support the big game of the week on Monday Night Football.

And so we had a climb. Are you ready? Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Come on, Hank. I mean, are you ready? I mean, are you really ready? Are you ready for some football?! That made its way into the thing.

Well, it’s timeless music and that’s what, in my mind, marks your compositions—the fact that they are timeless. Even if you play them today, they do have that sound that would fit in really well with the current television landscape. Thinking about the music that you composed for game shows in the seventies and eighties…one of the things I notice about them is that they tend to be easily separated in that the first segment could be the main theme, the bridge could be the ticket plug, or if there’s some music that needs to be played while they describe something.

Yep.

Is that a purposeful design technique? Are you the first person to compose television music in that sort of tight and efficient way?

I would say absolutely. Well, let’s take The Price is Right, which is a good example because it’s on every day. There’s the sweep of the audience, right? So in inventing the themes, (I’m) going to these places as they’re just blocking and learning how to run the show before music, and I’m studying what I want to do. I would do a piece of music like, you know, the come-on-down music. That was a timed thing, where they had to like, work their way out of the audience and thread their way around knees and run down all excited. Sometimes we would try to put an ending on it, to land it.

Then we have the walk-across. Many shows have the walk-across. When you introduce somebody, maybe at the beginning of a show…okay, it’s Whoopi Goldberg on the View, and she comes up and walks over to her chair. That was brought out of the composition that I would create. It’s heard if the theme plays long enough past the main part and into the bridge, or another development section,.

Then we’d have shorter pieces, which might be called the billboards. “Today’s exciting show is brought to you by Chevrolet”, or it’s brought to you by you know, Whirlpool or a soap or something. But that would be the billboard music. And that would be sort of related to, but not necessarily the same (as the main theme).

A bumper. That means we’ll be back after this message. Boom, we play ’em. Or “welcome back”, the rejoin. So we had names for all these things. They’ve become standard in the business now, you know? So, you know, “walk across”, “main theme”, “opening theme”. There was a hokey sound to (game show) music, and then we were lucky enough to be given the chance with some young producers—guys that would take a chance. You know, we were lucky to have guys that believed in us and would go that way and would let us do things.

One other show comes to mind, which is not a game show. Andy Lack, who was a producer and worked at CBS, said, “I want a jazz show. It’s gotta come from the street. At that time, David Sanborn (played) fabulous, fabulous alto sax. So I said, “We need that. We need a screaming sax in our theme.” So we did the West 57th Street theme with him, and it opened up with electronic drums. No one was using electronic drums.

I do a weekly podcast with the National Archives of Game Show History, and that’s housed at the Strong Museum up in Rochester. In the process of doing that show, I’ve talked to a lot of people who have worked with Mark Goodson and they have all confirmed something that I learned about Goodson early on—the fact that he was such a perfectionist. I wonder if you could relate to me your experience working with him in the context of his perfectionism. How many drafts of a composition did you write for him? Did he trust what you wrote right off? How many suggestions did he give?

I did one thing very early on. I think the show was I’ve Got a Secret. They were bringing that back with Steve Allen, remember? The comedian, pianist, right. And Steve was kind of badmouthing, “ah, you got this new kid. Who’s this guy?” And, and I, I did that and I, think Password was one of the first things I did for Mark.

But that was a Moog thing, which was a one at a time (composition). The Moog played one note at a time. You could play passages, but it didn’t play chords. You tune it as a bass, then you tune it as the melody, and then a counter melody, harmony against that. And then of course I had keyboards, I had the Hammond organ there, I had the piano, I had the guitars. And (the Moog) would even create a little kind of electric drum (sound), which was unique. No one was doing that.

Yeah, there was a tongue-click percussion kind of thing to that Password theme.

Right. And all that was was white noise going through a sequencer, back and forth, back and forth. That started Mark, like, “Hey, who’s this kid?” He was a perfectionist, but if there’s anyone more anal retentive than Mark, it’s me.

I mean, I would fuss over things. Well, this thing about Steve Allen, I came back and, and Steve heard it and he said, “damn, who’s that kid?” And cuz Steve wanted to write the theme, you know, cuz (game show themes a)re very lucrative when they play. But he said, “oh no, no, I’ll be the host. Get this kid in here.”

I would say that Mark knew I was enchanted with his style. We fit together very, very nicely because…yes, he was a perfectionist and yet, what was I doing? He’d be in the booth, he’d look up, and I’d be on the stage counting the steps from just off-camera up to where Bob Barker would stand. And when he said, “what are you doing?” I said, I’m timing the music. So he just looked away. He said, “Go for it, kid. Go for it.”

I treated every show, if it was sports, or news, or games, as a movie to score, which includes sad, mad, and glad. The Price is Right. Okay. It’s a car; that’s big. It’s a vacation; that’s big, and maybe has a Hawaiian flair, or a Spanish flair, or a European flair, or a South American flair. If it was a lamp, or if it’s Campbell’s soup, I had a formula from my jazz experience of starting big with the music, which would be a separate theme for the car or for the vacation or for the bedroom suite. That would be medium size. But I would do the scoring that way.

And economically, you start with a full band, let’s say 40 pieces. And you say, “okay, let’s get rid of the woodwinds”, or “let’s do this with the woodwinds”. “Let’s give the brass and the strings a break.” This would be all woodwinds in the rhythm section. “Now let’s bring the brass back, get rid of the woods,” or “let’s just have the strings.” And that would be your different sizes, because there was a personality for each one of those. So there might be 15 different themes, cuz you don’t want the same one for the same car. You got maybe three cars in a show.

I was scoring and making a mood and emotion for each thing we were doing. Of course, you know, game shows are fun. There’s very little very little bad, sad, mad, glad. There was a lot of glad in it. We did another show called Two-Minute Drill…that was timed, which was a lot of tension.

Double Dare, by the way—when they had the physical challenge. That was very, very time sensitive. We did it down at WHYY, the public television facility in Philadelphia. I was familiar with the downtown Philadelphia area because of the music school. So I went in there and I said, “This is Beat the Clock.” You know, like, “how much time do you get for this event?” Of course it was for kids and they had Super Sloppy, and they had the slime and they would have barrels of chocolate syrup or, you know, potatoes…I mean, just crazy stuff. The producers were just…I mean, they were young guys and they would be reliving their childhood about being messy.

Marc Summers was the host. He was a page for Mark Goodson on his shows, and when they were looking to hire a host, he called me. He said, “Edd, Edd, Edd, I gotta be a host. I, I, I, I’ve worked my whole life hanging around game shows to be a host. Can you, can you vote for me?” I said, ‘Well, Marc, I think you’re great. You know, you got a great look. You got enthusiasm, and you’re a stinking kid.” I think Marc Summers is fabulous. He really studied his craft. And I appreciated that because he’s an anal retentive like the rest of us. But he was good, you know? He knew everything and he had great delivery, great timing. So I’m so glad he developed a great career of that.

You named the Double Dare theme song after him, didn’t you? Isn’t the title On Your Marc?

Yeah. That was something I worked out with Marc. “Okay. Marc, how long did it take you to say that? Okay.” I had a great run at doing commercials. I mean, you know, thirties, fifteens, sixties, and it went on to become infomercials, but your basic commercial is 15, or 30, or 60. But, you know, if we knew that the, that the Obstacle Course was gonna be 60 seconds and finish, then that was so easy for me because of the commercial training…you know, to start building at 45 seconds in so that the excitement was building. “Is he gonna make it, is he gonna make it, is he gonna get the last flag? Oh, he almost made it!”

Like you said, game show compositions tend to reflect the mood of the show. Game show music is happy. Music like something for World News Tonight is a little more serious, a little more authoritarian.

Yep.

With that in mind, how would you rank the theme song to Jeopardy? Removing the iconic element of the melody, because everybody knows it as a game show theme, how well do you think the theme to Jeopardy does in conveying the mood of that show?

Well, it has become such a dog whistle, and that was Merv Griffin that wrote that, and of course Merv is no longer with us. But I would see him at various events. He was a big BMI writer and he was a big band crooner, but he had a great way with melody and harmony. He would always give credit to the music, that it did capture the show. And I don’t think there’s any way you could ever take that away. You know? I knew it; I appreciated it. There’s a captured feeling that I think is is appropriate. They’ve tried a few times to modernize it and make it rock-y or new, and I think they, they have a new arrangement of the, of the end music now. But it’ll always be Merv Griffin’s theme.

So musically, I think…well, an example. Okay, I’ll be egotistical. I’ll say The Price is Right as a theme that I created. I first played that, by the way, in my little studio before going to London to record the first go around on the Hammond organ. Mark would never rerecord it. We recorded it at a place called Pye Studios in the middle of London. It was mono because it was so early that stereo was not on TV. I would say, “Mark, let me modernize it now.” (Mark would reply) “It’s magic. Don’t touch it.” Well, then Bob Barker retired and they brought in Drew Carey, and Drew said…you know, he’s kind of a quick witted, fast talker. He said, “What is this mono stuff? I mean, the mono, are you kidding me? At least give me stereo.” And I heard they went to, you know, eight to 10 music composer guys to redo my theme in Los Angeles, and they couldn’t ever get the sound of that first day. I mean, there’s so many miniature, minuscule little parts. Unless you have a classic Moog, you’re never going to get that sound. They had to come to me and say, “Well, we need you to do this in stereo.”

I said, “well, yeah. It’s gonna cost you.” I mean, you know, because it’s a band. You know, this is not the modern era of samples. This is real guys playing. So (to) my New York guys, I said, “could you guys listen to this?” The guys that did the original date in London, I guarantee they created magic. We re-listened to it. And, you know, the band is so exceptional. The guys that played it back here, Andy Schnitzer and Jimmy Hines and the bass player Francisco Santana. I mean, they got it. They got it and nailed it. And that’s what’s on the air now.

And by the way, it’s in stereo. So that was redoing something. So if you go back to what makes the magic of what Merv Griffin created…he got the spirit. That was his show. He invented that.

You know, I am an enjoyer of music, and as I get older, I’ve started learning about other genres of music. You know, things other than pop. And this was the first year of my Spotify Wrapped that I’ve listened to more jazz than anything else. I’ve learned a lot in recent years about the jazz fusion movement that took over in Japan in the late seventies, early eighties. There are bands like Yellow Magic Orchestra, jazz fusion groups like Casiopea. musicians like Masayoshi Takanaka. It’s a whole world of music that, in retrospect, sounds a lot like it could be music on The Price is Right. It has the same sort of quality. They use a lot of the same instruments. There’s a lot of synth. I wonder if there are any tangible influences there. Were you influenced by any of the jazz fusion that was coming out of Japan around that time?

Not really. I mean, through the years, there was (David) Sanborn and Freddy Hubbard. (John) Coltrane, of course, is already gone. Not Japanese fusion, but the ones they listened to were, like, Bitches Brew with Miles, and Chick Corea. So I’d say that was more of an influence than the Japanese guys. I’d say that there’s certainly influence of, you know, Keiko Matsui right now.

I love the instruments, like the koto. You know, I made friends with the traditional instruments of Japan. We did the Nagano Olympics and I said, “I gotta have a koto in here.” It was a woman from Japan who was a classic koto player. I mean, we had an interpreter, but she knew some English. She was the concert woman. And the…oh, what are they called? The big drums. Those huge drums that they would play. I forget the name of ‘em.

Oh, taiko drums.

Thank you! We learned those, and that became the opening Larry Cam was the the producer, I think he was at ABC. He was a great believer in innovative sounds. It was exciting to ha to have those instruments, and to bring them into my studio and play them. We wound up having a form of fusion, I guess, in that we were open to all that. It’s really exciting.

This new album seems to come at a time when a lot of these vintage production elements are sort of coming back in vogue. There are a lot of disco elements that are creeping back into popular music. There are a lot of, you know, faux vintage videos and filters and that old VHS aesthetic. I’m sure it’s been fun for you to sort of sit back and watch those things come back into fashion, and it has to be equally as fun knowing that you were one of the originators of that sound. This album is a sort of testament to that.

I mean, how lucky was I to be given the freedom to do it? And, you know, having people believe in my ability and, and then appreciate it. I’m a lucky guy. Really. You know, you look back and you say, “wow, it was the era, it was the time.” It was when television was reinventing itself and Television City was starting to really be…I mean, that was when you’d hear “From Television City in Hollywood!” We took over that stage. It was just…what a blessing to be a part of that. And to have a guy like Mark Goodson who was…he wasn’t just games. I mean, he was the king of games.

And Dr. Moog! You’d see this little gray hair sticking out of a sleeping bag. He’s sleeping on the floor of a little office space. What a blessing. And I said, “Dr. Moog, how do you do it?” He says, “I just want to use my mind.” He didn’t become a multimillionaire. He just wanted to use his mind. I would be floating on air just because I was around this guy. Same way with Mark Goodson. It wasn’t the money, it was the chance they gave me, believing enough in me to take their time to hire me or teach me something.

I’ll give you one more, and then I’ll let you go. You know, musicians love sound, the sound of things. So we had a thing called the Moogerfooger—because it was the Moog Fogger, the white noise sound source. Mooger Fogger. Right? And I made that word on a label maker, and I put it on a big clear area (on the Moog module). And Moog comes in because he used to hang out at my studio and he was in town. We tune up the oscillators and make sure everything was perfect for the Moog because they would drift. And he stands there and he looks, and he goes,”Mooger…fooger?” I said, “yes, Dr. Moog, it’s the Mooger Fooger. It’s your name.” He says, “Can I use that?” And there’s now, in the repertoire of Moog spinoffs, a, Moogerfooger module that you can buy.

That’s wonderful. Cory, I think we have the title for our article. Edd Kalehoff: A Real Moogerfooger.

(laughs) Yeah, that’s it!

Edd Kalehoff’s new album Moog Grooves can be pre-ordered on vinyl through Sifted Sand Records or via Bandcamp. To learn more about Edd’s life and work, watch his in-depth interview with the National Archives of Game Show History at the Strong Museum of Play here.