#tbt: Tiger Electronics

In this edition of Throwback Thursday, Christian Carrion looks at some of the electronic game show adaptations of the mid-1990s and 2000s.

Throughout its history, the television game show has, to some degree, equated to the American dream for millions of viewers. The medium provides a hook on which hopeful potential winners can hang their hat, whether it be the fantasy of being called to come on down, the achievement of making it a true Daily Double, or the timeless goal of winning the million dollars. Of course, it’s many more people that have wished to accomplish these tasks than have actually had the chance. Like any lottery that dangles a golden carrot before its hungry, hopeful contenders, the game show endlessly teases the idea of a genuine dream come true; make it here and you, too, can win big! As any casting producer would tell you, though, getting on a game show requires just a bit more than a dollar and a dream. Every year, only hundreds of participants are selected from the tens, thousands, hundreds of thousands of applicants game show production companies receive each year. What’s a contestant to do?

In realization of this eternally tantalizing prospect, toy and game companies have, for decades, capitalized on the licensing of America’s most popular game shows, in an effort to bring the dream to the viewer and make him or her a contestant right from home. Sure, most of the popular games of the 50s, 60s and 70s have had dozens of editions of their board game snagged from shelves, but a plastic Rol-O-Matic puzzle board and cardboard prize tags can only go so far in the endeavor to capture the glitz and glamour of a real live game show. Where’s the music? The lights? The dulcet tones of the hosts we’ve come to admire Monday through Friday, and in turn, throughout our lives? With partial thanks to the ever-expanding home electronics industry, your good friends at Tiger Electronics have the answer.

They weren’t the first, though. As explained in a previous edition of Throwback Thursday, GameTek (then known as The Great Game Company) in the early 1980s planned to release several game show adaptations for the revolutionary Atari Video Computer System, the 2600 for short. Previous attempts at digitizing the contestant experience such as Password Plus and Jeopardy for Milton Bradley’s 8-track powered Omni system proved unsuccessful and clunky without graphics output capability, but The Great Game Company, a division of a larger entertainment firm called IJE, sought to remedy that. The lone print ad released for this lineup of games promised true-to-life gameplay and sound effects for each of the advertised titles, classic shows like The Price Is Right, Tic Tac Dough, The Joker’s Wild, and Jeopardy. Unfortunately, these games never saw the light of day, but The Great Game Company would move on to bigger and better things in the form of blockbuster releases of Jeopardy, Wheel Of Fortune, and countless other big-ticket TV games for just about every PC and home console from the Apple II to the Nintendo 64.

Tiger Electronics, founded in 1978 by Arnold, Gerald, and Randy Rissman, found early success with their 2XL, a toy robot that played rudimentary multiple-choice games via audio cassette. Any game-playing kid from the 80s and 90s, however, would most likely know the Tiger brand for its exhaustive line of handheld LCD games. Armed with relentless market research and the knowledge of what was popular with kids of their era, Tiger came out swinging on behalf of the families who perhaps couldn’t afford a Game Boy or Game Gear. A Tiger handheld, self-contained (as in, no cartridges necessary), typically cost between $10 and $15 less than its more fully-featured Nintendo or Sega counterpart. While the games were, by design, simplistic, Tiger made a killing by licensing huge pop culture properties, from Star Wars to the NFL to Full House to Sugar Ray Leonard to The Hunchback of Notre Dame. As the capabilities of LCD technology increased, it became possible for the company to squeeze entire game show experiences, questions and all, into a pocket-sized electronic device, thereby allowing wannabe contestants to live the dream on the go. Let’s take a look at some of these games, released from 1995 through the mid-2000s by Tiger Electronics.

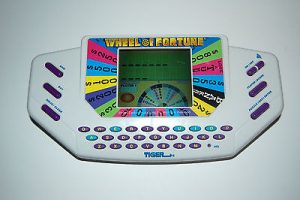

Wheel Of Fortune/Jeopardy!

Naturally, the two most popular syndicated game shows were the first to receive the Tiger treatment. Wheel Of Fortune and Jeopardy are textbook examples of the early Tiger aesthetic: in the absence of necessary on-board memory, material was crammed onto proprietary cartridges that plugged into the rear of each unit. This enabled Tiger to release new puzzles and clues for these games in perpetuity, although in reality no more than a dozen or so new cartridges were ever released.

Naturally, the two most popular syndicated game shows were the first to receive the Tiger treatment. Wheel Of Fortune and Jeopardy are textbook examples of the early Tiger aesthetic: in the absence of necessary on-board memory, material was crammed onto proprietary cartridges that plugged into the rear of each unit. This enabled Tiger to release new puzzles and clues for these games in perpetuity, although in reality no more than a dozen or so new cartridges were ever released. In Jeopardy’s case, the game unit came with a printed book through which players had to flip to find the corresponding category number and multiple-choice clue as dictated by the game itself. In later years, the game would no longer rely on a paperback supplement, as technology now allows thousands of clues to fit on a handheld unit no larger than a deck of cards. Wheel Of Fortune got a tech upgrade down the road as well–the latest full-size handheld version features an actual spring-loaded trigger that flicks to spin the on-screen wheel.

In Jeopardy’s case, the game unit came with a printed book through which players had to flip to find the corresponding category number and multiple-choice clue as dictated by the game itself. In later years, the game would no longer rely on a paperback supplement, as technology now allows thousands of clues to fit on a handheld unit no larger than a deck of cards. Wheel Of Fortune got a tech upgrade down the road as well–the latest full-size handheld version features an actual spring-loaded trigger that flicks to spin the on-screen wheel.

The Price Is Right

1998 saw the premiere release of the handheld version of the classic CBS game. While the unit itself was designed to be handheld, Tiger’s Price Is Right was best played on a tabletop. The game made extensive use of prize cards and game numbers (again, backed up by a cartridge). Players were instructed to enter the serial number for each prize to be bid on, as well as a secondary Pricing Game card once the one-bid prize was won. Very few pricing games featured in this version of Price; some of the more popular visually intensive games like Plinko were omitted due to the unit’s dedicated six-segment numerical displays. Future electronic versions of The Price Is Right by Irwin Toys retained the prize-card mechanics, but added other goodies like an actual Showcase Showdown wheel and miniature Plinko board.

1998 saw the premiere release of the handheld version of the classic CBS game. While the unit itself was designed to be handheld, Tiger’s Price Is Right was best played on a tabletop. The game made extensive use of prize cards and game numbers (again, backed up by a cartridge). Players were instructed to enter the serial number for each prize to be bid on, as well as a secondary Pricing Game card once the one-bid prize was won. Very few pricing games featured in this version of Price; some of the more popular visually intensive games like Plinko were omitted due to the unit’s dedicated six-segment numerical displays. Future electronic versions of The Price Is Right by Irwin Toys retained the prize-card mechanics, but added other goodies like an actual Showcase Showdown wheel and miniature Plinko board.

Hollywood Squares

As the Tom Bergeron-hosted version of the celebrity panel show began to gain popularity, Tiger released electronic Hollywood Squares in 1999. Gameplay remained intact from the original series, including the Secret Square bonus prize. A good portion of the unit’s screen was dedicated to displaying cool pixel art of the face of each celebrity in the squares. Also worth mentioning is the quality of the writing contained within the unit’s game book, with joke answers that were actually kind of hilarious:

As the Tom Bergeron-hosted version of the celebrity panel show began to gain popularity, Tiger released electronic Hollywood Squares in 1999. Gameplay remained intact from the original series, including the Secret Square bonus prize. A good portion of the unit’s screen was dedicated to displaying cool pixel art of the face of each celebrity in the squares. Also worth mentioning is the quality of the writing contained within the unit’s game book, with joke answers that were actually kind of hilarious:

Q: Who wrote the songs “Yummy Yummy Yummy” and “Chewy Chewy”?

A: Mike Tyson

Family Feud

Before the success of the current syndicated Feud, Tiger released a handheld adaptation decked out in the Ray Combs-era needlepoint and white-on-blue lighting motif. This game featured two big juicy lock-in buttons for contestants to slap in the Face-Off. Also featured was a random electronic coin-flip mode to determine who answers first when playing against the computer, since it wasn’t possible for the AI opponent to buzz in. Questions were, as was clearly the standard for Tiger quiz games of the era, printed in a supplementary game book and individually numbered for easy access by the computer’s memory system. At some point, Tiger also released a travel version of this game in more of a pocket-easel form factor, as well as more question book/cartridge combos.

Before the success of the current syndicated Feud, Tiger released a handheld adaptation decked out in the Ray Combs-era needlepoint and white-on-blue lighting motif. This game featured two big juicy lock-in buttons for contestants to slap in the Face-Off. Also featured was a random electronic coin-flip mode to determine who answers first when playing against the computer, since it wasn’t possible for the AI opponent to buzz in. Questions were, as was clearly the standard for Tiger quiz games of the era, printed in a supplementary game book and individually numbered for easy access by the computer’s memory system. At some point, Tiger also released a travel version of this game in more of a pocket-easel form factor, as well as more question book/cartridge combos.

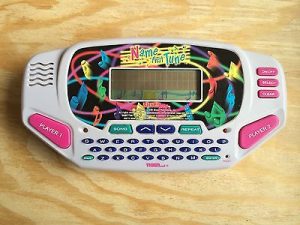

Name That Tune

Tiger’s Name That Tune wasn’t the first electronic version of the perennial music identification quiz–Castle Toys released a battery-gobbling dinosaur of a product in 1980, complete with play money, 32 pre-programmed songs, and a rudimentary editor with which a user could input his or her own songs. This much smaller and more efficient version, released in 1997, added the same rubberized QWERTY keyboard previously employed by Wheel Of Fortune so that players could actually type in the title of the tune they were naming, in addition to arrow keys to select a number for the Bid-A-Note portion of the game. Songs were stored via cartridge, and the rules carried over from the most recent TV edition, hosted by Jim Lange.

Tiger’s Name That Tune wasn’t the first electronic version of the perennial music identification quiz–Castle Toys released a battery-gobbling dinosaur of a product in 1980, complete with play money, 32 pre-programmed songs, and a rudimentary editor with which a user could input his or her own songs. This much smaller and more efficient version, released in 1997, added the same rubberized QWERTY keyboard previously employed by Wheel Of Fortune so that players could actually type in the title of the tune they were naming, in addition to arrow keys to select a number for the Bid-A-Note portion of the game. Songs were stored via cartridge, and the rules carried over from the most recent TV edition, hosted by Jim Lange.

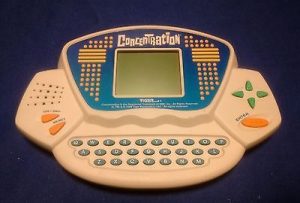

Concentration

The release of Concentration in 2000 marked a slight change in aesthetic for Tiger’s game show line, typefied by unusually sharp attention to detail. The handheld version of Concentration featured the Edd Kalehoff-composed theme music from the 1970s Jack Narz-hosted incarnation, as well as the actual “ka-clunk” sounds of the old trilons turning. The board contained 16 squares which concealed random words to be matched by the players (either head to head or against the computer player). Rebuses were beautifully rendered on the LCD display. The game also featured the bonus round from the more recent Classic Concentration. Instead of matching cars or prizes, the bonus round challenges the player to match various shapes in exchange for a bonus added to their point total. It’s hard to imagine there was such a massive demand for a portable Concentration at this point in time, which makes one wonder if “one of us” was lucky enough to score a high-level position at Tiger back in the day.

The release of Concentration in 2000 marked a slight change in aesthetic for Tiger’s game show line, typefied by unusually sharp attention to detail. The handheld version of Concentration featured the Edd Kalehoff-composed theme music from the 1970s Jack Narz-hosted incarnation, as well as the actual “ka-clunk” sounds of the old trilons turning. The board contained 16 squares which concealed random words to be matched by the players (either head to head or against the computer player). Rebuses were beautifully rendered on the LCD display. The game also featured the bonus round from the more recent Classic Concentration. Instead of matching cars or prizes, the bonus round challenges the player to match various shapes in exchange for a bonus added to their point total. It’s hard to imagine there was such a massive demand for a portable Concentration at this point in time, which makes one wonder if “one of us” was lucky enough to score a high-level position at Tiger back in the day.

Super Password

On the subject of awesome games that literally no one asked for, here’s Super Password. Released over a decade after the cancellation of the NBC series and the death of its host, Bert Convy, Super Password greets the user with a few seconds of the 1960s Password theme before getting right into the first puzzle. The game contains hundreds of puzzles on its included cartridge, but it’s unclear if any additional cartridges were offered for sale. Gameplay is faithful to the series, save for the fact that the player is always the receiver of the clues due to technical limitations.

On the subject of awesome games that literally no one asked for, here’s Super Password. Released over a decade after the cancellation of the NBC series and the death of its host, Bert Convy, Super Password greets the user with a few seconds of the 1960s Password theme before getting right into the first puzzle. The game contains hundreds of puzzles on its included cartridge, but it’s unclear if any additional cartridges were offered for sale. Gameplay is faithful to the series, save for the fact that the player is always the receiver of the clues due to technical limitations.

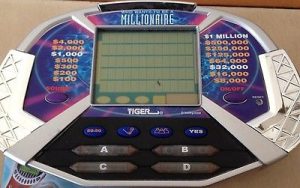

Who Wants To Be A Millionaire

Licensing a home version of Millionaire in the year 2000 was essentially a license to print money, and Tiger was front and center with their handheld version of the ABC quiz show. While the large screen did a great job of displaying the questions and choices, and the light-up answer buttons were colorful and looked similar to the on-screen graphics used on the show, the voice of Regis Philbin left much to be desired. Throughout the game, the title of the show and the classic “Is that your final answer?” were delivered in a nasally, Anotado-esque Philbin impression that was more funny than accurate. Also, the Ask The Audience lifeline tended to display randomly-generated results, meaning that the audience almost never had the correct answer. The guts of this game were also shoehorned into a larger Tabletop Edition that same year.

Licensing a home version of Millionaire in the year 2000 was essentially a license to print money, and Tiger was front and center with their handheld version of the ABC quiz show. While the large screen did a great job of displaying the questions and choices, and the light-up answer buttons were colorful and looked similar to the on-screen graphics used on the show, the voice of Regis Philbin left much to be desired. Throughout the game, the title of the show and the classic “Is that your final answer?” were delivered in a nasally, Anotado-esque Philbin impression that was more funny than accurate. Also, the Ask The Audience lifeline tended to display randomly-generated results, meaning that the audience almost never had the correct answer. The guts of this game were also shoehorned into a larger Tabletop Edition that same year.

Let’s Make A Deal

And now for something completely different. Breaking away from the handheld form factor, tabletop Let’s Make A Deal was a gargantuan specimen, a replica of the set of the classic game show complete with boxes, curtains, and prizes. Prize cards were numbered and stuck out of the 6 box and curtain compartments. The prizes were ordered in such a way that no numerical input was needed; the voice of Monty Hall would guide you through the game, and it would all just make sense as long as the cards were in the right order. Built-in drawers on either side of the set would hold the prize cards and play money for safe keeping. The game even included the zonk music from the 1984 version, easily one of the best losing pieces of music written for any game show. This one sells for between $30 and $60 on eBay and Amazon, but is well worth the investment if you’re into that sort of thing.

And now for something completely different. Breaking away from the handheld form factor, tabletop Let’s Make A Deal was a gargantuan specimen, a replica of the set of the classic game show complete with boxes, curtains, and prizes. Prize cards were numbered and stuck out of the 6 box and curtain compartments. The prizes were ordered in such a way that no numerical input was needed; the voice of Monty Hall would guide you through the game, and it would all just make sense as long as the cards were in the right order. Built-in drawers on either side of the set would hold the prize cards and play money for safe keeping. The game even included the zonk music from the 1984 version, easily one of the best losing pieces of music written for any game show. This one sells for between $30 and $60 on eBay and Amazon, but is well worth the investment if you’re into that sort of thing.

The Weakest Link

One of the lesser-known Tiger releases, The Weakest Link is one of the most elaborate electronic games the company has ever designed. The unit itself contains 60 double-sided circular question cards, one of which is used per round. After the code on the card is entered (prompted by the actual voice of Anne Robinson), the mechanical question holder “rewinds” the card to question 1 and starts the clock, accompanied by all the original music stings from the BBC/NBC series. All questions are multiple choice, and a player can hit buttons A, B, C, or BANK when their turn is up. Also intact is the final head-to-head round to determine the day’s winner. Video of Tiger’s Weakest Link in action can be found here:

One of the lesser-known Tiger releases, The Weakest Link is one of the most elaborate electronic games the company has ever designed. The unit itself contains 60 double-sided circular question cards, one of which is used per round. After the code on the card is entered (prompted by the actual voice of Anne Robinson), the mechanical question holder “rewinds” the card to question 1 and starts the clock, accompanied by all the original music stings from the BBC/NBC series. All questions are multiple choice, and a player can hit buttons A, B, C, or BANK when their turn is up. Also intact is the final head-to-head round to determine the day’s winner. Video of Tiger’s Weakest Link in action can be found here: