#tbt: Number Please

In this edition of Throwback Thursday, Christian Carrion takes a look at a game show based on hangman. No, not that one.

In 1961, three years after the cancellation of its primetime edition on CBS, time was running out on the ABC daytime show Beat The Clock. Since its move from radio to television in 1950, the classic stunt game, hosted by original Superman voice actor Bud Collyer, had given away truckloads of Polaroid cameras, a toy store’s worth of Roxanne dolls, acres of Sylvania television units, and thousands upon thousands of dollars in cash (much of which was won during the era of the Super Bonus Stunt, inspired by the big-money quizzes of the day). Of course, Bud and company also dealt out their fair share of cream pies, faces full of seltzer water, broken teacups, hula hoops, airborne balloons, traffic cones, cardboard tubes, jump ropes, beach balls, umbrellas and tennis rackets.

In 1961, three years after the cancellation of its primetime edition on CBS, time was running out on the ABC daytime show Beat The Clock. Since its move from radio to television in 1950, the classic stunt game, hosted by original Superman voice actor Bud Collyer, had given away truckloads of Polaroid cameras, a toy store’s worth of Roxanne dolls, acres of Sylvania television units, and thousands upon thousands of dollars in cash (much of which was won during the era of the Super Bonus Stunt, inspired by the big-money quizzes of the day). Of course, Bud and company also dealt out their fair share of cream pies, faces full of seltzer water, broken teacups, hula hoops, airborne balloons, traffic cones, cardboard tubes, jump ropes, beach balls, umbrellas and tennis rackets.

After eleven years, during which thousands of couples emerged from the studio audience to try their hand at various wacky games, the old clock had run its course. Bud Collyer signed off Beat The Clock for the last time at 12:57pm on January 29, 1961. Viewers had no need to fear for the fate of America’s number-one clock watcher, however, as he wouldn’t go unemployed for long. Over that weekend, he made the transition from timed stunt solicitor to word puzzle purveyor. That following Monday, in the same 12:30pm time slot occupied just three days ago by Beat The Clock, Bud Collyer greeted ABC viewers as the host of Number Please.

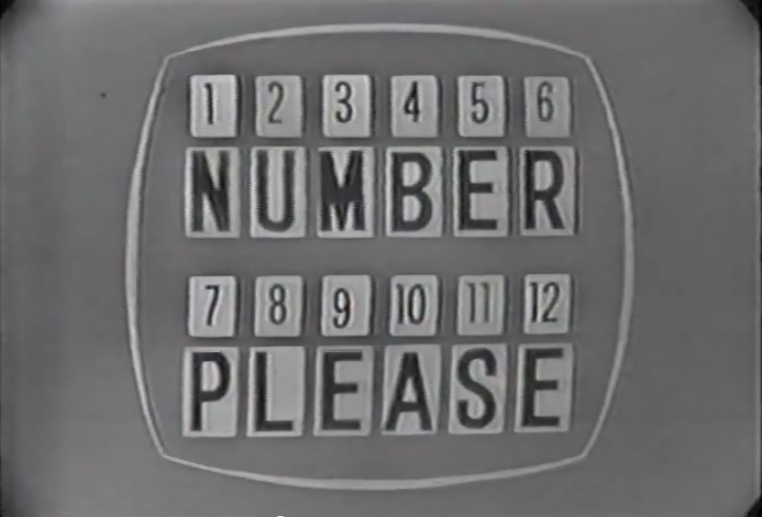

The game was based on the children’s game of hangman, an idea that would be considerably improved upon fourteen years later. On Number Please, two contestants battled each other in a friendly round of puzzles reminiscent of an old-time parlor game. The players faced a board consisting of two rows of 20 numbered backlit squares, each row belonging to one contestant by name. To start the game, each player would call out three free numbers, which in turn lit up to reveal letters in their rows; each row contained the name of a prize. Accompanied by an organist playing escalating notes to build suspense (because, after all, it is an early-60s game show), the players would alternate turns picking one number at a time, revealing either a letter or a space in their respective rows. At any point, a player could buzz in and stop the action if he or she knew the answer to their own puzzle. Host Collyer would ask the contestant to solve the puzzle, and then to repeat their solution to make sure everyone concerned heard correctly. If correct, the player then had the opportunity to solve his or her opponent’s puzzle. The contestant won the prizes named in the puzzles, accompanied by a bonus prize that tied the two together—for example, the puzzles CONCERTO BY MOZART and BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY would yield two classical records and a home stereo system to play them on.

The game was based on the children’s game of hangman, an idea that would be considerably improved upon fourteen years later. On Number Please, two contestants battled each other in a friendly round of puzzles reminiscent of an old-time parlor game. The players faced a board consisting of two rows of 20 numbered backlit squares, each row belonging to one contestant by name. To start the game, each player would call out three free numbers, which in turn lit up to reveal letters in their rows; each row contained the name of a prize. Accompanied by an organist playing escalating notes to build suspense (because, after all, it is an early-60s game show), the players would alternate turns picking one number at a time, revealing either a letter or a space in their respective rows. At any point, a player could buzz in and stop the action if he or she knew the answer to their own puzzle. Host Collyer would ask the contestant to solve the puzzle, and then to repeat their solution to make sure everyone concerned heard correctly. If correct, the player then had the opportunity to solve his or her opponent’s puzzle. The contestant won the prizes named in the puzzles, accompanied by a bonus prize that tied the two together—for example, the puzzles CONCERTO BY MOZART and BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY would yield two classical records and a home stereo system to play them on.

Number Please was one of the many shows to come from the legendary game show production team of Mark Goodson and Bill Todman. In the early 60s, more than likely as a means to remain viable in the climate of mistrust that lingered around game shows following the quiz scandals that had just died down a couple of years prior, the spirit of experimentation had taken hold of the Goodson-Todman people—they were taking risks which, in retrospect, were very progressive and daring. For starters, Number Please, which appealed mainly to housewives who were home in the early afternoon, was the only game show on the air at that time to regularly feature male prize models. The show was also one of the few Goodson-Todman projects that weren’t scripted series or variety hours. Possibly in an effort to protect the company as the big-money game show house began to fall, Goodson-Todman tried to extend their empire to traditional drama and entertainment programming, starting with Goodyear Theatre in 1957 and Philip Marlowe in 1959. The experiment, ultimately, was unsuccessful, and except for That’s My Line, a That’s Incredible!-flavored blip on the reality TV radar hosted by Bob Barker in 1980, Goodson and company stuck to their day job.

Number Please was one of the many shows to come from the legendary game show production team of Mark Goodson and Bill Todman. In the early 60s, more than likely as a means to remain viable in the climate of mistrust that lingered around game shows following the quiz scandals that had just died down a couple of years prior, the spirit of experimentation had taken hold of the Goodson-Todman people—they were taking risks which, in retrospect, were very progressive and daring. For starters, Number Please, which appealed mainly to housewives who were home in the early afternoon, was the only game show on the air at that time to regularly feature male prize models. The show was also one of the few Goodson-Todman projects that weren’t scripted series or variety hours. Possibly in an effort to protect the company as the big-money game show house began to fall, Goodson-Todman tried to extend their empire to traditional drama and entertainment programming, starting with Goodyear Theatre in 1957 and Philip Marlowe in 1959. The experiment, ultimately, was unsuccessful, and except for That’s My Line, a That’s Incredible!-flavored blip on the reality TV radar hosted by Bob Barker in 1980, Goodson and company stuck to their day job.

Another experiment involved the musical score for the show. While live music on game shows typically happened at specific, rehearsed moments in the game—when a player won, when it was time to go to commercial, when the credits rolled—the organist on Number Please happily played away throughout the show, even while Bud interviewed the contestants or made small talk with the camera. As well as providing a constant musical score, the organist also doubled as a sort of sound effects guy—in one episode, the organist quickly slides his hand across the keyboard when Collyer mentions the habit of some drivers to swing way out into the intersection when they make a turn. In fact, Goodson and Todman were playing with the music on several of their shows in the early 60s; for instance, on the other side of Manhattan, their NBC game Say When!! was doling out prizes to housewives in Studio 6A at Rockefeller Center while two electric guitarists strummed away, for the first time ever on a game show. In later years, Goodson-Todman would overhaul the stodgy, violin-laden music on most of its game shows—The Price Is Right, The Match Game, and To Tell The Truth (Collyer’s other hosting gig in the 60s, on CBS) would all receive the Score Productions treatment in the 60s.

Another experiment involved the musical score for the show. While live music on game shows typically happened at specific, rehearsed moments in the game—when a player won, when it was time to go to commercial, when the credits rolled—the organist on Number Please happily played away throughout the show, even while Bud interviewed the contestants or made small talk with the camera. As well as providing a constant musical score, the organist also doubled as a sort of sound effects guy—in one episode, the organist quickly slides his hand across the keyboard when Collyer mentions the habit of some drivers to swing way out into the intersection when they make a turn. In fact, Goodson and Todman were playing with the music on several of their shows in the early 60s; for instance, on the other side of Manhattan, their NBC game Say When!! was doling out prizes to housewives in Studio 6A at Rockefeller Center while two electric guitarists strummed away, for the first time ever on a game show. In later years, Goodson-Todman would overhaul the stodgy, violin-laden music on most of its game shows—The Price Is Right, The Match Game, and To Tell The Truth (Collyer’s other hosting gig in the 60s, on CBS) would all receive the Score Productions treatment in the 60s.

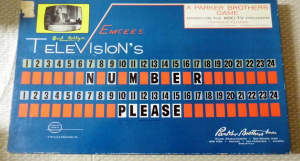

For viewers who were used to watching the zany antics of Beat The Clock, seeing Bud Collyer and two contestants sitting at a plain desk, accompanied by a rather static shot of an unmoving board, was a bit of a shock. The game itself was incredibly sedate, even by early-60s TV standards. Nevertheless, Number Please remained popular throughout 1961—so much so, in fact, that Parker Brothers released a home version of the game, with Bud’s picture on the box. By the end of the year, however, the show began to wear out its welcome, and on December 29, 1961, Bud Collyer, the ubiquitous organist, and Number Please were issued their walking papers.

For viewers who were used to watching the zany antics of Beat The Clock, seeing Bud Collyer and two contestants sitting at a plain desk, accompanied by a rather static shot of an unmoving board, was a bit of a shock. The game itself was incredibly sedate, even by early-60s TV standards. Nevertheless, Number Please remained popular throughout 1961—so much so, in fact, that Parker Brothers released a home version of the game, with Bud’s picture on the box. By the end of the year, however, the show began to wear out its welcome, and on December 29, 1961, Bud Collyer, the ubiquitous organist, and Number Please were issued their walking papers.

Despite the cancellation, Bud remained on television as host of CBS’ To Tell The Truth until its demise in 1968. In addition to his television duties, he was a spiritual man—he taught Sunday school at his church in Greenwich, Connecticut for more than 35 years, as well as recorded an album of readings from the New Testament, contributed to several religious literary works, and authored two inspirational books, Thou Shalt Not Fear (1962) and With The Whole Heart (1966). He was married to the 1930s film actress Marian Shockley, with whom he had three children (two of which appeared disguised as impostors on their dad’s show). He was approached by Goodson and Todman in 1969 to host a new version of To Tell The Truth that was gearing up to go into syndication, but Bud just wasn’t up to it—his poor health at that time had prevented him from taking any more television work. Bud Collyer died of complications related to a circulatory ailment on September 8, 1969 at the age of 61. Coincidentally, Collyer’s death occurred on the same day the new To Tell The Truth premiered across the country, hosted by Garry Moore, who got Collyer’s personal blessing before accepting the job as emcee.

Despite the cancellation, Bud remained on television as host of CBS’ To Tell The Truth until its demise in 1968. In addition to his television duties, he was a spiritual man—he taught Sunday school at his church in Greenwich, Connecticut for more than 35 years, as well as recorded an album of readings from the New Testament, contributed to several religious literary works, and authored two inspirational books, Thou Shalt Not Fear (1962) and With The Whole Heart (1966). He was married to the 1930s film actress Marian Shockley, with whom he had three children (two of which appeared disguised as impostors on their dad’s show). He was approached by Goodson and Todman in 1969 to host a new version of To Tell The Truth that was gearing up to go into syndication, but Bud just wasn’t up to it—his poor health at that time had prevented him from taking any more television work. Bud Collyer died of complications related to a circulatory ailment on September 8, 1969 at the age of 61. Coincidentally, Collyer’s death occurred on the same day the new To Tell The Truth premiered across the country, hosted by Garry Moore, who got Collyer’s personal blessing before accepting the job as emcee.

Television is an evolutionary medium, constantly adapting to survive in different climates among new breeds of predators. Even still, some of the most interesting stories television history has to offer come from those formative years, when ideas were constantly shuffled in and out of the box as the people in charge gradually learned what their new audiences wanted. Number Please may not be the most memorable entry in the Goodson-Todman catalog—or the most exciting—but it sure does rank among the most interesting.